From Monroe’s warning to Trump's seizure of Maduro

Unveiling the Donroe doctrine

James Monroe buried the lede.

The fifth U.S. president waited until the end of the tenth paragraph of his seventh annual message to Congress to pronounce the foreign policy principle that still bears the name of the “Monroe Doctrine.”

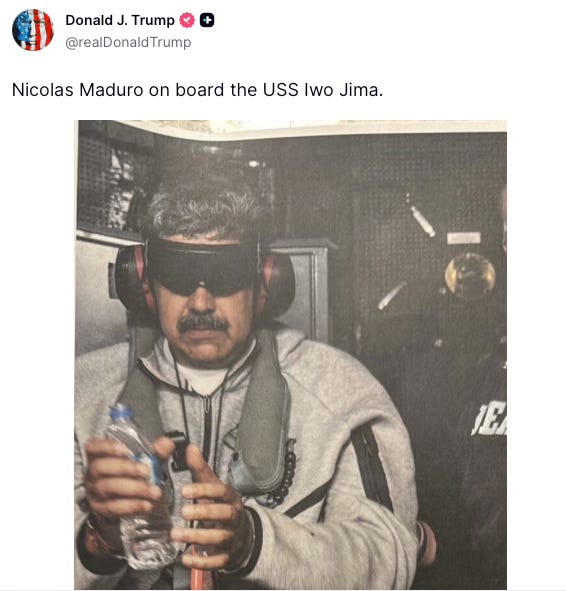

It was a far cry from today’s Mar-a-Lago press conference, where President Donald Trump and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth crowed over the U.S. military’s seizure of Venezuela’s dictator Nicolás Maduro to face criminal charges — and the president approvingly noted the coining of a “Donroe Doctrine.”

In Monroe’s message on December 2, 1823, he updated Congress and the American people on diplomatic discussions with the British, French, Russian and Spanish governments. Then he drew a big red line.

“The American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.”

The United States favored “liberty and happiness” for those engaged in wars in Europe, and empathized with the Greeks fighting for independence. But, in those battles, “we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy so to do.”

“It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected…” Then Monroe announced, “we should consider any attempt” by European nations “to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.”

It would be decades before his words would be officially described as the Monroe Doctrine. This principle would become the basis for America’s stance toward Latin America as it eventually evolved under Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and now Donald Trump.

The “hands off our hemisphere” caution to European nations became, under the “Roosevelt corollary,” a muscular justification for gunboat diplomacy — active U.S. intervention in the affairs of our southern neighbors.

Then, on November 18, 2013, President Barack Obama’s secretary of state, John Kerry junked the paternalistic tradition of American dominance in the hemisphere. To an applauding audience at the Organization of American States, Kerry announced, “The era of the Monroe Doctrine is over.”

The relationship would now be “about all of our countries viewing one another as equals, sharing responsibilities, cooperating on security issues, and adhering not to doctrine, but to the decisions that we make as partners to advance the values and the interests that we share.”

In seizing Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro and bombing his nation’s capital on January 2, Trump revived the Monroe Doctrine.

“It was dark, the lights of Caracas were largely turned off, due to a certain expertise that we have,” the president said. “It was dark and it was deadly.” No Americans were killed, no U.S. equipment lost in the operation, he said.

“We’re going to run the country till such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition,” said Trump. “We want peace, liberty and justice for the great people of Venezuela.”

Maduro was widely considered the loser of the last election, but he remained in power nonetheless. He apparently didn’t see the U.S. attack coming; the Wall Street Journal reported December 29 that “in recent weeks, the 63-year-old leftist has been dancing on stage at rallies, calmly strolling trade expos and attending Christmas tree lightings hand-in-hand with his wife. He has serenaded supporters with dance remixes and offered up his own rendition of John Lennon’s Imagine…”

Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores are facing criminal charges in the U.S. for “their campaign of deadly narcoterrorism against the United States and its citizens,” said Trump. American energy companies will go into Venezuela to revive the ailing oil industry, according to the president, who complained that it had stolen the “massive oil infrastructure” built by American companies.

In his national security strategy released last fall, Trump had set the stage by positing a “Trump corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, promising to “enlist established friends in the Hemisphere to control migration, stop drug flows, and strengthen stability and security” while “cultivating and strengthening new partners while bolstering our own nation’s appeal as the Hemisphere’s economic and security partner of choice.”

At the Mar-a-Lago news conference, Trump said, “American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again.” He added, “We have to be surrounded by safe, secure countries.”

In its campaign to oust Maduro, the Pentagon struck boats it alleges were carrying drugs and cartel members, killing more than a hundred people without providing evidence of their supposed wrongdoing. It also demolished a remote dock on Venezuela’s coast. The U.S. Navy blockaded oil tanker traffic from Venezuela. An armada of U.S. ships, led by the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford, sailed to the region.

It’s far too early to assess the impact of Maduro’s seizure on Venezuela, Cuba, Latin America and the world. Does a U.S. President’s assertion of dominance over America’s neighbors encourage the leaders of Russia and China to insist on the same status over their own neighbors? And if so, what does that mean for Ukraine, Eastern Europe and Taiwan?

A pair of diplomats

The original Monroe Doctrine owed much to the experience and humility of its two authors: Monroe and his secretary of state John Quincy Adams. While they were zealous defenders of U.S. national interests and advocates of territorial expansion, they had a layered view of the push-and-pull of diplomacy and of the risks of military adventures.

It’s hard to think of a U.S. president and secretary of state who were better suited to conducting foreign policy. Monroe had represented the U.S. in France and Britain. Adams served as minister to the Netherlands, Prussia, Russia and Britain.

When they drafted the words that would become the Monroe Doctrine, the U.S. was intent on preventing an alliance of major European powers from intervening in the struggles over newly independent nations that were Spain’s former colonies in Latin America.

Simón Bolívar, born in Caracas in 1783, became the continent’s version of George Washington by defeating an imperial power. “One man would be credited for single-handedly conceiving, organizing and leading the liberation of six nations,” including Venezuela, wrote Marie Arana in her 2013 biography of Bolívar.

It was a spectacular achievement, on a larger scale than the American Revolution, as Arana noted. The population was “one and a half times that of North America” and “the landmass the size of modern Europe.”

Monroe gave diplomatic recognition to Colombia in 1822 and set up a mission there the following year. The present-day nations of Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia and Panama were then part of a Colombian federation; they would later become independent countries.

Not seeking ‘monsters to destroy’

In 1821, on the 45th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence — his father was one of the 56 signatories — John Quincy Adams gave an extraordinary speech in Washington. After the declaration was read aloud, the secretary of state said the document would forever be “a beacon on the summit of the mountain…a light of admonition to the rulers of men, a light of salvation and redemption to the oppressed.”

America, dedicated to “equal liberty,” has “respected the independence of other nations while asserting and maintaining her own. She has abstained from interference in the concerns of others…”

Adams, who would succeed Monroe as president in 1825, added, “Wherever the standard of freedom and independence, has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy.”

An overly aggressive foreign policy would risk much, Adams warned: “She might become the dictatress of the world. She would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit.”

Here are links to: Monroe’s message, Adams’ speech, Kerry’s speech, Trump’s national security strategy and the Wall Street Journal’s report on Maduro.

Outstanding, Rich. It appears that in President Trump's close reading of the Monroe Doctine, he neglected this sentence as it appears in your column: "But she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy.” Then, again, U.S. policy regarding South and Central America now is to be known as the "Donroe Doctrine," according to the president, and may depart from the original.

Useful historical context. I remember as though it were yesterday then-Secretary of State John Kerry declaring the Monroe doctrine defunct and dead, with cooperative partnerships among equals in the hemisphere to succeed it. Even if somewhat high-minded and unrealistic, it made a lot of sense. The context had changed, and American heavy-handedness was seen as counterproductive. (Lots of low-burning residual "anti-Americanism" throughout the region sure to break out into open flame again.). For the last 30 years or so following the end of the Cold War, the United States had opened a new chapter of quiet diplomacy, the bygone gunboat stuff seeming almost cartoonish in retrospect. So now we return to the cartoon, because it had worked so well in the past and because the cartoon image corresponds so perfectly with external reality. At least three questions remain outstanding: What does this mean for Venezuela itself? What does it mean for the region and the US relationship with our neighbors (a number of whom are not thrilled by the gunboat style and dubious about the dominance and supremacy of the United States in "our" hemisphere)? And what does it mean for the new world order, which will presumably be a bit like the sphere of interest order that led to several great global collisions. By that time, however, our dear leader will be gone, and the deluge will have little to do with him. So nice to know about history so as to better appreciate how little we have learned from it. Or perhaps there's something to the theory that once the people who knew better have all died off, the new people have to learn the same lessons all over again, with a new twist of the slightly different circumstances including technology etc. Nicely done.