How Jimmy Carter avoided checkmate

Mideast peace lessons for Trump

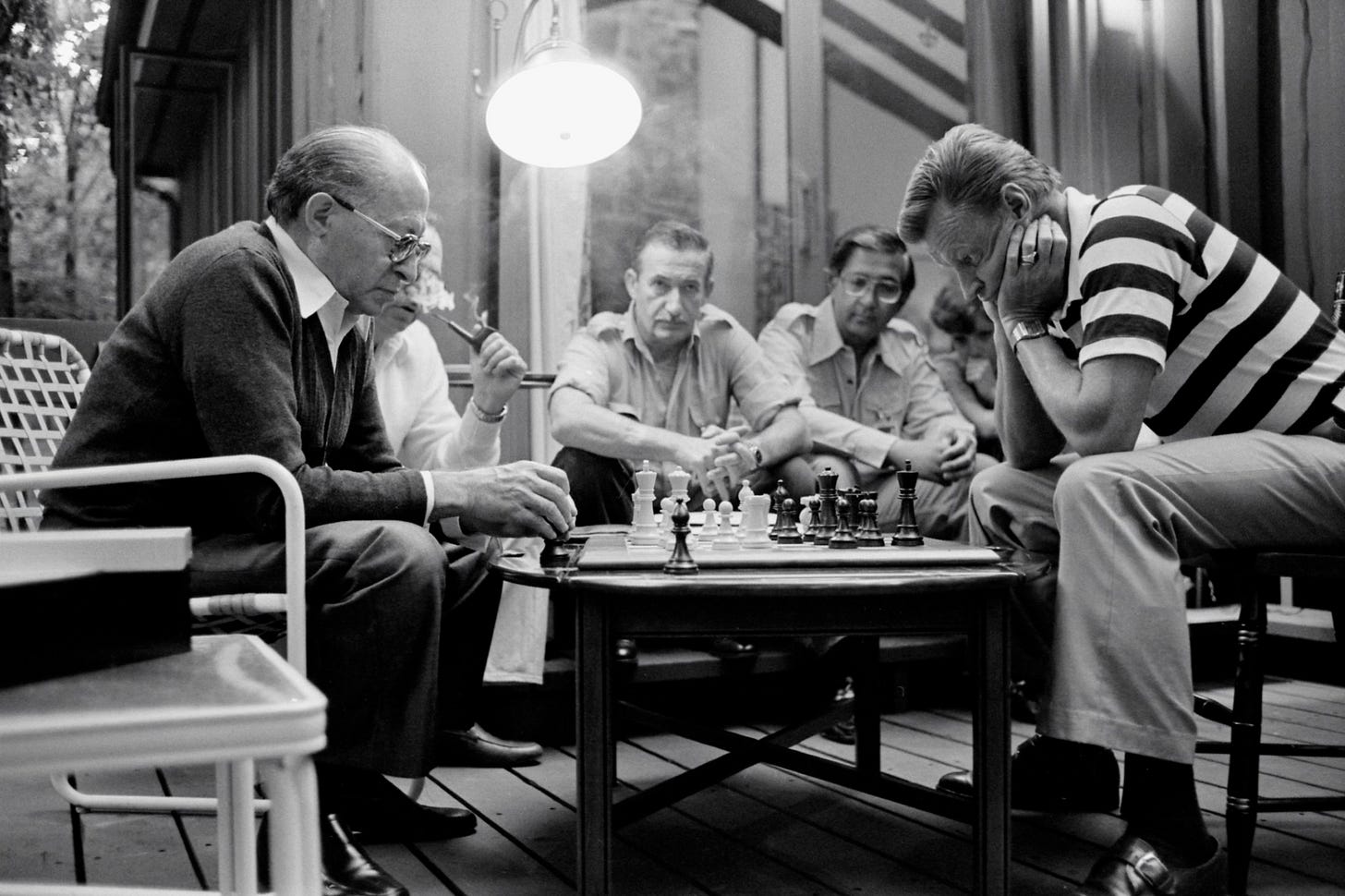

One afternoon during the Camp David peace summit in September, 1978, U.S. national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski walked over to the presidential retreat’s Birch cabin and challenged Israel’s prime minister Menachem Begin to a chess game.

Begin accepted. But to lower expectations, he told Brzezinski he hadn’t played chess since the day in 1940 when Soviet security police arrested him in a crackdown on Zionists.

“It was a highly charged match: two Polish expatriates facing one another, each with a reputation for ruthless strategic brilliance,” Lawrence Wright wrote in his book Thirteen Days in September. “Begin identified Brzezinski with the Polish feudal lords who had made life so miserable for the Jews back in Brisk [Brest-Litovsk]. Brzezinski’s Catholic…