ICE's tough-guy moment fails disastrously

Two are dead as agents trample over the Constitution

Police Captain Frank Pape cultivated a reputation in the 1950s and early 60s as Chicago’s “toughest cop.”

“Pape has been in 15 gun battles in which nine hoodlums were killed,” wrote James Gavin in the Chicago Tribune on April. 17, 1960. Detective magazines ran 49 articles about him, including an interview with Coronet in which he declared, “I’m not going to take any lip from a hoodlum.”

When Pape died in March, 2000 at the age of 91, his New York Times obituary said he was responsible for sending 300 men to prison and five to the electric chair. It noted that he “bragged that he never used his gun to fire warning shots, only to kill.”

But according to Gavin’s story in the Tribune, Pape wasn’t only a tough guy. “He has been known to lend money to hoodlums just released from state prison.” When the detectives on his squad started quarreling, Pape knew just what to do. He would soothe their tempers with an invitation to his mother’s cottage in a northern Illinois lake region. There Pape would ply them with beer and hamburgers and break out into a “tenor rendition of My Wild Irish Rose.”

Pape’s legend was so well burnished that he became one of the models for Detective Lt. Frank Ballinger, Lee Marvin’s character in the television show, M Squad. That portrayal in turn became the inspiration for Lt. Frank Drebin, the character played by Leslie Nielsen in the satirical Police Squad! TV series and the Naked Gun movies.

It seems that you had to be named Frank to matter at the cop shop.

There was an underside to the career of Frank Pape. It was reflected in a case that was not mentioned in the Chicago Tribune puff piece — a story of flagrant police violations of civil liberty that led the U.S. Supreme Court to open the door to decades of lawsuits aiming to compensate people who were denied their constitutional rights.

The landmark case revealed that Pape and his officers searched a home without a warrant, dragged a naked couple out of bed in front of their children, allegedly used racial epithets and struck the children.

Those kinds of abuses by law enforcement stand in the spotlight today, after two U.S. citizens were killed in Minneapolis by ICE agents during protests against the agency’s aggressive policies.

Masked agents traveling in unmarked cars have terrorized the city while political leaders defending ICE accuse the victims — without evidence — of being terrorists or assassins. ICE asserts that its agents can enter the homes of those facing deportation orders with only an administrative warrant, and without having a warrant signed by a federal judge.

In Minneapolis the abuses have been widespread. The New York Times reported that “federal agents were seen dragging a man from his home in St. Paul. The man was later identified as ChongLy Scott Thao, a Hmong immigrant and naturalized U.S. citizen with no criminal record, according to his family. Mr. Thao and his family said that the armed agents did not present a warrant or allow him to show identification at the time of arrest…

“A widely shared video taken in Minneapolis shows immigration agents dragging a woman, later identified as Aliya Rahman, from her car, after one agent shattered the window on the passenger side.”

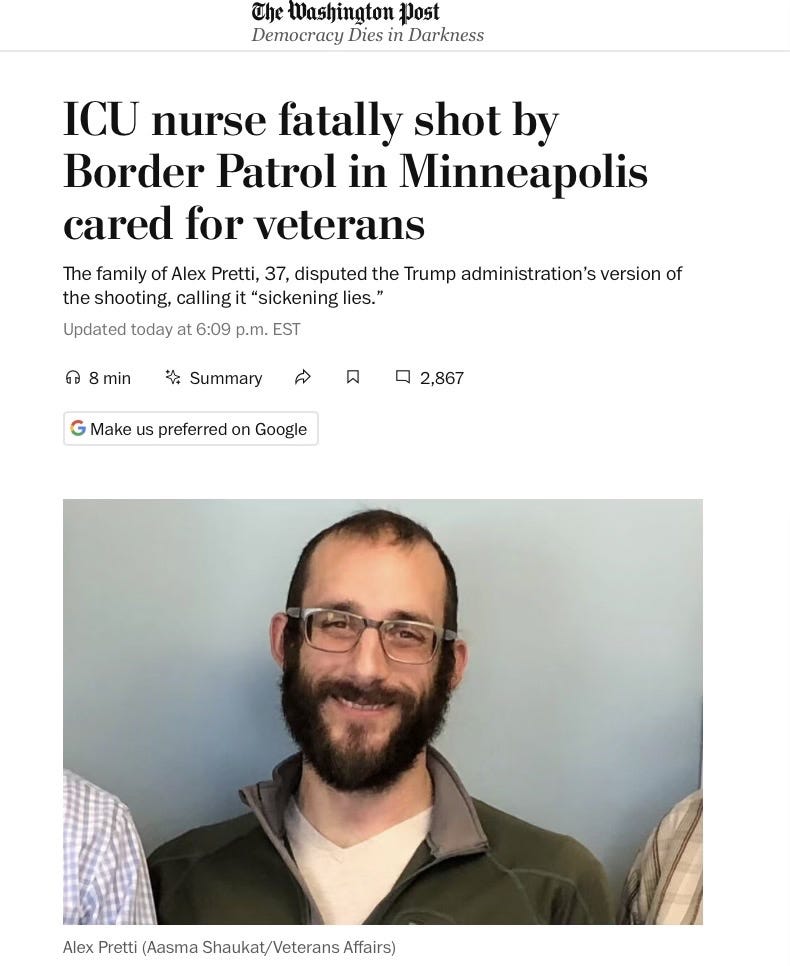

In the deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, videos taken at the scenes appeared to contradict the Trump administration’s account of the killings.

On Monday, January 26, the national furor over those killings — with some Republicans joining Democrats in criticizing ICE — sparked signs of a change of direction in Washington.

The Wall Street Journal, citing unnamed administration officials, said controversial Border Patrol Commander Gregory Bovino “will imminently leave Minnesota along with some of his agents.” President Donald Trump is sending border czar Tom Homan to Minneapolis. The president said he had productive phone conversations with Gov. Tim Walz and Mayor Jacob Frey.

The “tough guy” moment in Minneapolis proved to be a disaster for Trump.

The Pape reality

The Tribune’s 1960 article was headlined, “Capt. Frank Pape, Chicago’s Toughest Policeman, Proves to Be a Soft Touch.”

No one had told that to James and Flossie Monroe, a young couple living with their six children at 1424 South Trumbull Avenue in Chicago.

The lives of the Monroes were turned upside down as a result of the murder of insurance agent Peter Saisi on the evening of October 27, 1958.

“When the police arrived at the scene,” Federal District Judge James B. Parsons wrote, the victim’s wife, Mary Saisi “explained that two Negro men had entered her home and killed her husband. She stated that the men had escaped with a sum of money and a number of white dress shirts.”

The next day, Mrs. Saisi was summoned to Central Police Headquarters to review photos of potential suspects. Shown a picture of the 30-year-old James Monroe, she said, “It looks like him.”

When Chicago’s “toughest cop,” Deputy Chief of Detectives Frank Pape signed on for duty at midnight, he was briefed on the investigation and ordered eight members of the police department to meet him between 5 and 6 a.m. near Monroe’s home.

Everyone arrived at the specified meeting spot that early morning. “No one had secured or attempted to secure either an arrest or a search warrant,” Judge Parsons noted. “All of them were attired in citizen’s dress. Pape briefed his men on their project and designated the positions they were to take. Then, in four unmarked squad cars, they proceeded to 1424 South Trumbull Avenue.”

When Pape knocked on the back door of the basement apartment, one of the children turned on the light. Pape showed his badge and asked where Monroe was; the child told him that his father was in the front bedroom.

Pape would later describe the events of that morning as a “very routine arrest,” with the only glitch coming when a child protested and Pape shoved him away, according to law professor Myriam Gilles, who wrote a compelling account of the case in 2007.

The judge told the rest of the story this way:

Pape led the way down the long hallway and into the dark bedroom. Turning on his flashlight, he found James and Flossie Monroe in bed. Monroe was ordered out of bed and taken into the front room. Monroe was either totally naked or clothed only with a T-Shirt. Mrs. Monroe was allowed to pull a blanket about herself as she was gotten out of the bed by one of the officers...

Several of the officers who had been stationed outside gained entry through the front door. The closets, furniture and mattresses were searched for white dress shirts and weapons, but none were found. During this flurry of activity, all members of the family were aroused. The children began crying and hollering, and some began yelling abusive language at the officers in an effort to attract the officers’ attention. One of the older boys, who was especially vocal in his denunciations of the officers, received a sharp blow to the head. He fell back against his brother, and the two of them falling crushed their bed to the floor. One of the smaller boys tripped over one of the officers as he attempted to run to his father’s side. Mrs. Monroe’s daughter attempted to leave the apartment for the purpose of ‘calling the police’, but she was restrained. Pistols were drawn. Heated comments were flung about. Threats of killing were uttered.

According to Monroe’s civil rights complaint, he was “forced to stand in the center of his living room naked. Another officer ordered Mrs. Monroe out of bed. She refused, explaining that she was naked. The officer dragged her out and pushed her into the living room. Chief Pape was questioning Mr. Monroe. He kept calling him ‘n—r’ and ‘black boy,’ and hit him in the belly with his flashlight several times.” After police searched the house, emptying drawers and ripping open mattresses, Monroe was allowed to dress. His hands were cuffed and he was taken to the police station.

When Monroe appeared in a lineup on October 29, Mrs. Raisi “was unable to identify him.” The same thing happened later that day when Monroe was placed in a lineup in front of the victims of a recent spate of robberies of cab drivers. Finally, Monroe was released without any charges.

The real story of the murder became clear a month later. Monroe had nothing to do with it. As Gilles wrote, detectives found “Mary’s rumored boyfriend, Richard Lansing. Lansing immediately confessed to murdering Peter Saisi, provided police with the murder weapon, and implicated Mary as a co-conspirator for providing him $45 to purchase the .25 caliber revolver and for planning the entire thing in order to collect on her husband’s $25,000 life insurance policy.”

Both were convicted; Lansing was sentenced to life in prison and Mary Saisi received a 60-year sentence.

Water and bananas

Frank Pape joined the Chicago Police Department in 1933. To make the minimum weight requirement of 150 pounds, he had followed his Uncle Charley’s advice to “drink a lot of water and eat a lot of bananas.” Pape’s father, an immigrant from Germany, had died when he was nine.

Chicago in the 1930s was a glorious stage for a young ambitious cop. Pape and fellow officers “wore fedoras and natty suits and carried Tommy guns on raids,” according to a Toronto Globe & Mail article cited by Myriam Gilles. While Pape found success in locking up gangsters, everything went wrong one day when his squad spotted men who appeared to be “casing” a bank.

Morrie Friedman, who was Pape’s partner, fired a warning shot. One of the suspects fired back, wounding Friedman in the stomach. He died in Pape’s arms. That was the origin of Pape’s vow to always shoot to kill, according to Gilles.

Pape thrived in a department that would become notorious for its lawbreaking. Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge “and detectives under his command,” the New York Times wrote in a 2018 obituary, “were accused of extracting confessions from more than 100 people while questioning them in the 1970s and ’80s by shocking them with cattle prods, smothering them with plastic typewriter covers and pointing guns in their mouths while pretending to play Russian roulette. Most of the suspects were black; he was white.”

Monroe v. Pape

Lower courts dismissed the civil rights complaint filed by attorney Donald Page Moore on behalf of James and Flossie Monroe, saying it should be filed in state rather than federal court. The Monroes chose instead to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. That would change history.

Writing for an 8-1 majority in 1961, Justice William O. Douglas upheld the Monroes’ right to sue the police officers who burst into their home.

Douglas cited Section 1983 of the federal code:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.

That language dated back to 1871, as a result of a message to Congress from President Ulysses S. Grant. The Ku Klux Klan was terrorizing blacks in the south who had been freed as a result of the Civil War and state officials were letting it happen. Grant wrote: “A condition of affairs now exists in some States of the Union rendering life and property insecure and the carrying of the mails and the collection of the revenue dangerous.” The law that resulted was named the Ku Klux Klan Act.

States had the means to restore order but they were choosing not to use them. “It is abundantly clear,” Justice Douglas wrote, “that one reason the legislation was passed was to afford a federal right in federal courts because, by reason of prejudice, passion, neglect, intolerance or otherwise, state laws might not be enforced and the claims of citizens to the enjoyment of rights, privileges, and immunities guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment might be denied by the state agencies.” Thus, it was only in 1961 as a result of the court ruling that a law passed in 1871 began to give most victims of police abuse an avenue to recover damages.

A crucial distinction is that Section 1983 only applies to abuses committed by state officials. It does nothing to stop ICE, or any part of a rogue federal government, from violating the Constitution.

But it did help the Monroe family. A jury awarded the parents $13,000 for their civil suit against several police officers, with $8,000 of that amount applying to Pape. He paid the judgement, didn’t appeal and left the police force for a time. Pape later sued TIME Magazine for libel for describing the Monroes’ account of the arrest as facts rather than allegations; the U.S. Supreme Court found that he couldn’t prove that TIME acted maliciously in its reporting.

Monroe v. Pape had far-reaching impact. The number of civil rights cases citing Section 1983 “jumped from the hundreds in the 1960s to more than 20,000 in the late 1970s, alleging a wide array of unconstitutional conduct, including mistreatment by police and prison guards, school segregation, First Amendment violations, and government policies that discriminated against women,” according to law professor Joanna Schwartz’s 2023 book Shielded: How the Police Became Untouchable.

After the Supreme Court’s 1961 Monroe v. Pape ruling, not every lawyer was enthusiastic about the revival of Section 1983. “Marvin Aspen, an attorney who defended the City of Chicago and its employees against civil rights suits, warned a classroom of Northwestern law students in the summer of 1966 that people were using Section 1983 to bring frivolous cases agains the Chicago police with the hope of ‘making a quick buck,’” Schwartz noted.

As the Supreme Court grew more conservative and police unions gained more power, checks were placed on the use of Section 1983.

Gregory Bovino

Gregory K. Bovino joined the Border Patrol 30 years ago, but became nationally known only recently as he led ICE deployments around the country. Bovino gained attention partly for his choice of garments, especially his overcoat, which the Department of Homeland Security says is standard issue.

As the Guardian noted, German media highlighted the authoritarian style conveyed by the coat. Süddeutsche Zeitung observed, “Other countries also had these coats, but Bovino’s outfits complete the Nazi look: a closely cropped haircut, as if he had taken a photo of [assassinated SA leader] Ernst Röhm to the barber.”

Others might argue that Bovino bears a closer resemblance to Sean Penn’s over-the-top portrayal of a federal military officer, Col. Steven J. Lockjaw, in the Oscar-nominated film One Battle After Another. In the film, Lockjaw develops an obsession with hunting down radical activists.

Bovino’s credibility has been questioned in court. “In September, a jury in Los Angeles acquitted a protester of assaulting a federal officer after the defense argued that officers, including Mr. Bovino, had lied about what happened,” the New York Times reported. “In November, a federal judge in Illinois concluded that officials, including Mr. Bovino, had lied about the actions of protesters. Of 100 people charged with felony assault on federal agents in four Democratic-led cities from May to December, 55 saw their charges reduced or dismissed outright, according to an Associated Press examination.”

The Times added:

On Tuesday, several police chiefs in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area held an unusual press conference: They said federal agents had stopped, along with local residents, some off-duty police officers ‘for no cause’ and asked them to prove their citizenship.”

Mark Bruley, the police chief of Brooklyn Park, a Minneapolis suburb, said chiefs had received “endless complaints” and that off-duty police officers—all people of color—had experienced the same treatment. In one case, he said, one of his officers was stopped as she drove past ICE. The agents boxed her in, knocked her phone from her hand when she tried to record them, and had their guns drawn, he said...

ICE says its operations are lawful and targeted.

“If it’s happening to our officers, it pains me to think of how many of our community members it is happening to every day,” Bruley said.

After agents fired 10 shots, killing 37-year-old protester Alex Pretti in Minneapolis on January 24, Bovino said the incident "looks like a situation where an individual wanted to do maximum damage and massacre law enforcement."

The Border Patrol commander later appeared at a press conference to claim that the shooting and others like it were the consequence of actions taken by protesters and state and local politicians.

"When someone makes the choice to come into an active law enforcement scene, interfere, obstruct, delay or assault law enforcement officer and — and they bring a weapon to do that. That is a choice that that individual made," Bovino said.

Some Second Amendment activists have criticized federal officials for arguing that legal gun owners shouldn’t carry their weapons to a protest.

But arguments like these aside, the central question is whether the law can hold federal law enforcement officers accountable if they deprive people of their constitutional rights.

Vice President J.D. Vance has asserted that the ICE officer who shot Renee Good has “absolute immunity.” White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller has said ICE agents have “federal immunity.”

The truth is that, like other law enforcement personnel, ICE agents aren’t immune to prosecution, though there are real hurdles to it. For one thing, the Trump team’s reflexive defense of the officers who fired shots suggests that the administration won’t conduct a thorough investigation. Moreover, the agents may well feel that Trump would pardon them if convicted of any federal crimes.

One key alternative to criminal prosecution of agents is to seek to hold them civilly liable for their actions.

But in Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 1982, the court ruled that most government officials, including police officers and other members of law enforcement are protected by “qualified immunity.”

Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., writing for the court, said, “We therefore hold that government officials performing discretionary functions, generally are shielded from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.”

In practice, courts have interpreted this standard to mean that officers cannot be held liable for wrongdoing unless there has been a published court case of almost identical circumstances.

“Courts have granted officers qualified immunity,” Schwartz wrote, “even when they have engaged in egregious behavior—not because what the officers did was acceptable, but because there wasn’t a prior case in which that precise conduct had been held unconstitutional.”

A family memory

On that day in 1958 when officers stormed into the home of James and Flossie Monroe, their eldest son Houston was turning 17.

In email exchanges with Joanna Schwartz, the author of Shielded, Houston Monroe remembered that “he and his brothers and sisters yelled at the tops of their lungs to alert the neighbors that officers had broken into their home. He believes that noise might have saved his stepfather’s life.”

“Those were killer cops that raided us,” Houston remembered. “If it wasn’t for the kids, they probably would have killed him.”