The first No Kings Day was 250 years ago

Thomas Paine’s ‘Common Sense’

On April 19, 1775, the first battles of the American Revolution broke out at Lexington and Concord. In Massachusetts, the event is still commemorated as Patriots’ Day.

On July 4, 1776, the political battle of the American colonies against Britain was officially declared in Philadelphia, and of course it is remembered yearly as Independence Day.

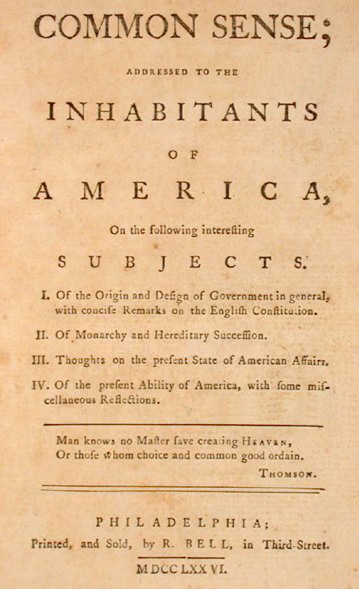

There was another monumental day along the road to independence that isn’t officially celebrated. It was 250 years ago — January 10, 1776. It could be called Common Sense Day, after the title of the pamphlet written by Thomas Paine and published then in Philadelphia.

When Paine took pen to paper, the colonists who resisted British rule were far from united on the course ahead. Should they risk a war against the world’s most powerful military? Or strive for the best settlement they could get from London?

In titling his essay Common Sense, Paine chose wisely. For in the see-saw battle over two opposed options, claiming that his demand for independence was simply “common sense” gave his arguments more weight. They seemed obvious — and irrefutable.

In truth, it was not at all clear that the colonists had any real chance of defeating the redcoats, or that they had the means to form some durable confederation that Paine would later enthusiastically describe as the “United States of America.”

Those obstacles didn’t deter Paine. In his pamphlet, he sought to demolish the case for reconciling with the British government — an idea he called a “fallacious dream.” He used ringing language that connected with ordinary readers — and there were many of those.

In its first three months, Common Sense sold 120,000 copies. By the end of the revolution, half a million had been sold, according to the National Constitution Center, which estimated that one in five colonists owned a copy. Translations appeared in France and other countries. Paine could have grown rich off the proceeds but he refused to accept pay for his writing in support of the revolution.

“Paine appealed to the unlettered — farmers, shopmen, mechanics— with an avowed intent to ‘make those that can scarcely read understand,’ wrote Rick Atkinson in The British Are Coming. “A Massachusetts reader declared, ‘every sentiment has sunk into my well-prepared heart.’”

To George Washington, Paine’s pamphlet provided “unanswerable reasoning.” John Adams differed, calling Common Sense a “crapulous mass” and its author “a mongrel between pig and puppy.”

Paine was neither kind of animal. A little-educated Englishman, the son of a corset-maker, he became an unlikely shaper of world events in the late 18th century, influencing both the American and French Revolutions.

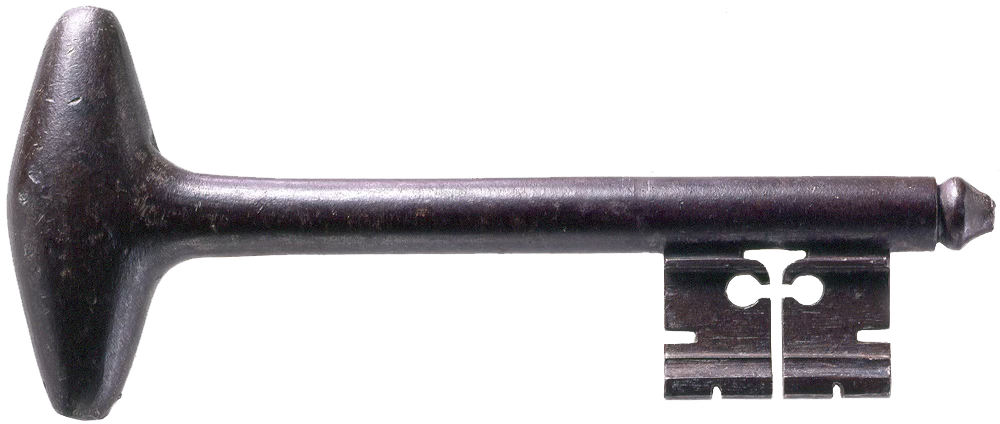

After the Bastille in Paris was liberated on July 14, 1789, the Marquis de Lafayette gave the key of the prison to Paine and asked him to send it to President George Washington. “The key hangs to this day on the wall of Washington’s home at Mount Vernon,” wrote Christopher Hitchens.

Common Sense was “the largest achievement in the history of pamphleteering” and “a catalyst that altered the course of history,” according to Hitchens, author of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man. It helped stiffen colonists’ resolve for independence. And its attack on monarchy in the person of King George would become the precursor of the anti-royal bill of particulars spelled out by Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence.

The cause of all mankind

Paine began his instant bestseller by grandly defining the stakes of the decision facing the colonies:

“The cause of America,” he declared “is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.”

Taking aim against the British system of government, he directed his fire at the hereditary monarchy, even though most of the decisions that infuriated the colonists came from Parliament rather than King George III.

Ever since the Norman invaders conquered England in 1066, that nation had “some few good monarchs” and “a much larger number of bad ones,” Paine noted. The kings tried to trace their legitimacy back to William the Conqueror, but he was a “usurper” and it wasn’t an “honorable” claim. “A French bastard landing with an armed banditti, and establishing himself king of England against the consent of the natives, is in plain terms a very paltry rascally original—It certainly hath no divinity in it.”

“A French bastard landing with an armed banditti” is a phrase you can easily imagine Michael Palin shouting in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. But for Paine’s purposes, it was also superbly useful rhetoric.

“One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of hereditary right in kings,” Paine wrote, “is, that nature disapproves it, otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule by giving mankind an ass for a lion.”

To Paine, as Christopher Hitchens observed, “the idea of a hereditary ruler was as absurd as the idea of a hereditary mathematician, and put the country at the continual risk of being governed by an imbecile. (The madness of King George Ill lent extra point to these observations.)”

Paine brings the issue down to a level everyone can appreciate: He says he wouldn’t have backed an “offensive war” against Britain because it would be “murder.”

But a defensive war is another matter. “If a thief breaks into my house, burns and destroys my property, and kills or threatens to kill me, or those that are in it, and to ‘bind me in all cases whatsoever’ to his absolute will, am I to suffer it? What signifies it to me, whether he who does it is a king or a common man; my countryman or not my countryman; whether it be done by an individual villain, or an army of them?”

As Hitchens wrote, Paine boiled down the choice to the simplest of terms: “Since separation was inescapable sooner or later, might not NOW be the time? And was it not the case that Americans were already strong and capable enough to do it?”

Paine tackled many practical issues, arguing that the colonies would have prospered even without their tie to Britain. He said that American trade would suffer every time England got involved in European wars. And he contended that the King’s government would never agree to fair terms if the colonists chose to remain part of the empire.

But Paine’s words soar as well: echoing the St. Crispin’s Day speech of Shakespeare’s King Henry V, he wrote, “Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it. Say not that thousands are gone, turn out your tens of thousands; throw not the burden of the day upon Providence, but ‘show your faith by your works, that God may bless you.’”

From England to America

Born in Thetford, a small town northeast of London, Paine struggled to make his way in life, both personally and professionally. Paine’s first wife died in childbirth; his second marriage, to the daughter of a tobacco shop owner, failed, along with Paine’s attempt to run the shop.

“Paine became a habitué of the working-man’s lecture hall and the freethinker’s tavern, where enthusiastic discussion groups were the yeast for self-improvement and political reform,” Hitchens noted. “He might, if the marriage had lasted, have become a well-found and humorous Whig: a red-faced local ‘character’, fond of a drop of brandy, with a fund of anecdote and a reputation as a bit of a rebel.”

What transformed Paine’s life was meeting Benjamin Franklin in London. The inventor and American statesman gave Paine letters of introduction to his son William, who was the governor of New Jersey, and his son-in-law Richard Bache, an insurance underwriter in Pennsylvania.

Franklin’s letter to Bache said:

Dear Son,

The bearer, Mr. Thomas Paine, is very well recommended to me, as an ingenious, worthy young man. He goes to Pennsylvania with a view of settling there. I request you to give him your best advice and countenance, as he is quite a stranger there. If you can put him in a way of obtaining employment as a clerk, or assistant tutor in a school, or assistant surveyor, (of all which I think him very capable,) so that he may procure a subsistence at least, till he can make acquaintance and obtain a knowledge of the country, you will do well, and much oblige your affectionate father. My love to Sally and the boys.

B. Franklin.

Once in Philadelphia, Paine met a bookstore owner who hired him as managing editor of his new publication, the Pennsylvania Journal. That role didn’t last long. Hitchens noted that Paine clashed with one of the magazine’s sponsors “who in revenge spread the rumour that Paine was a heavy drinker, a slur that clung to him throughout his life, most probably because it was partly true.”

Paine wrote Common Sense at the suggestion of Dr. Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia intellectual and fellow abolitionist. But Hitchens noted that the doctor urged Paine not to call for independence — an instruction that Paine immediately ignored.

After the success of Common Sense, Paine served in George Washington’s army. He was, Atkinson wrote, “a lanky man just shy of 40 with a high forehead, a tippler’s red nose which he often tickled with snuff, and blue eyes described as ‘full, brilliant, and singularly piercing.’”

The Crisis

In December 1776, after the continental army had retreated from Long Island, New York City and New Jersey and was settling in for a bleak winter, Paine began writing a series of pamphlets he called The Crisis. Again, he sought to be the voice of reassurance for the colonists, affirming that they had chosen right in going to war against King George.

“These are the times that try men’s souls,” Paine wrote. “The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph….”

After the colonies won their independence, Paine returned to England. He began his book, The Rights of Man, as a rejoinder to the British statesman Edmund Burke’s critique of the French Revolution.

When Paine “called for the spreading of the French Revolution across mainland Europe,” Hitchens wrote, “the gloves started to come off. Prime Minister William Pitt, on 21 May 1792, issued on behalf of the Crown a ‘Royal Proclamation’ aimed at ‘wicked and seditious writings’. On the same day Paine received a summons to appear in court and answer a charge of seditious libel.” He soon fled across the English Channel.

In Paris

At first, France greeted Paine warmly. He was given honorary citizenship and elected to the French National Convention. King Louis XVI had been deposed and was held captive by the revolutionaries. In 1792, Paine published a letter to the French people, proposing that they should “punish by instruction, not revenge.”

As Hitchens noted, “to the faction of Robespierre, Marat and Danton, these words sounded lame and feeble. They needed blood to water their liberty tree, and were not too choosy about whose blood that would be.”

Paine wrote more pamphlets expressing opposition to the execution of the king, then known by the revolutionaries as Louis Capet. “Paine’s argument was a classically liberal one,” Hitchens observed. “Public torture and execution was the problem, not the answer. It was the very signature of what France was trying to transcend, or to leave behind.”

Paine foresaw that a revolution that exterminates its enemies would eventually turn on itself. In rudimentary French, Paine spoke to the Convention in Paris, urging that Louis be imprisoned until the end of the revolution and then banished. The convention nevertheless voted to execute the king.

In 1793, Paine was arrested and imprisoned, escaping death only because a jailer put a chalk mark on the wrong side of Paine’s cell door. Soon after, Paine’s antagonist, the revolutionary leader Robespierre, was himself sent to the guillotine.

The arrival in Paris of James Monroe, the future president who was serving as a diplomatic representative of the Washington administration, led to Paine’s release.

“Monroe arrived at Luxembourg Prison to personally bring Paine back to his home,” wrote Tim McGrath in his biography of Monroe. “Bearded, bedraggled, and emaciated, Paine required help getting into the carriage. Monroe assured him he could stay ‘till his death or departure for America.’”

The latter option became real in 1802, when President Jefferson wrote to Paine. The old pamphleteer was able to live on the 300-acre New Rochelle farm he had been granted by the New York State Legislature in 1784 for his service to the revolution. But when Paine turned up to vote in a congressional election in 1806, local officials said he was not a citizen of the United States and wouldn’t let him cast a ballot.

Last years

Paine never regained his health. But he remained in touch with powerful figures, writing to Jefferson to propose buying the huge expanse of land from France that became known as the Louisiana Purchase. His opposition to organized religion of any denomination and his skeptical reading of the Bible—spelled out in his book The Age of Reason — helped marginalize Paine in the America of the 1800s.

When Paine died in Greenwich Village at the age of 72 in 1809, The New York Evening Post damned him with faint praise: “he lived long, done some good, and much harm.”

Paine’s words have lived on, helping inspire Parliamentary reform in England and the anti-slavery movement in the U.S. Lincoln, Roosevelt and Reagan were among the presidents who read and quoted Paine, wrote Hitchens.

“With its plain metaphors and its limpid logic, Paine's language implied that the mysteries of politics were not so mysterious at all, that even rude reasonable men could comprehend public affairs and act upon their comprehension,” historian Sean Wilentz has observed.

Only six people were present for Paine’s burial in New Rochelle. In a bizarre move a decade later, English journalist and activist William Cobbett dug up Paine’s forgotten grave and shipped nearly all his remains to England.

As a writer, Cobbett had been a pro-monarchist foe of Paine’s during the Revolutionary Era. But now he viewed Paine as a hero, wrote Heather Thomas for the Library of Congress in 2019.

Cobbett predicted that “…those bones will effect the reformation of England in Church and State.” Instead Cobbett became the butt of criticism and jokes for his grave robbery.

“According to legend,” Thomas wrote, “some of the bones were lost or destroyed, made into buttons, or sold off individually. Over the years, several people have claimed to be in possession of parts of the bones—a rib in France, a jawbone in England, a skull in Australia. The only part of Paine near his original burial site is a mummified brain stem and a lock of his hair, which were buried in a secret location by the historical association.”

In any event, the real memorial to Thomas Paine isn’t a dismembered skeleton, but a living thing — the nation he helped will into being with a 47-page pamphlet on that January day 250 years ago.

For more on the 250th birthday of the United States:

The midnight ride of Paul Revere, 250 years later

Paul Revere had already ridden through the countryside, warning of the hundreds of redcoats marching west from Boston.

Thank you for this thought-provoking piece. It brings Paine (back) to life.