The man who tried to rein in presidential war powers

Clement Zablocki's long battle

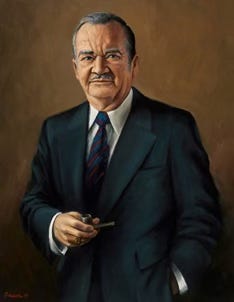

“A conciliator, not a firebrand.” That was how the New York Times’ Steven V. Roberts described Rep. Clement J. Zablocki in his obituary December 4, 1983. The Democrat from Milwaukee “preferred consensus to confrontation” and was known for “a bushy mustache he kept carefully clipped, and a tiny, leather-bound pipe he kept clasped in his hand.”

He also played a key role in the long history of disputes between presidents and Congress over who controls the power to go to war. Zablocki sponsored the War Powers Act, a 1973 law that surfaces whenever a president orders military action.

His career vividly demonstrates the potential for — and the limits of — congressional control of war powers.

After U.S. bombers struck three targets in Iran Saturday, the Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer said, “We must enforce the War Powers Act.” He insisted, “No president should be allowed to unilaterally march this nation into something as consequential as war with erratic threats and no strategy.”

Sen. …