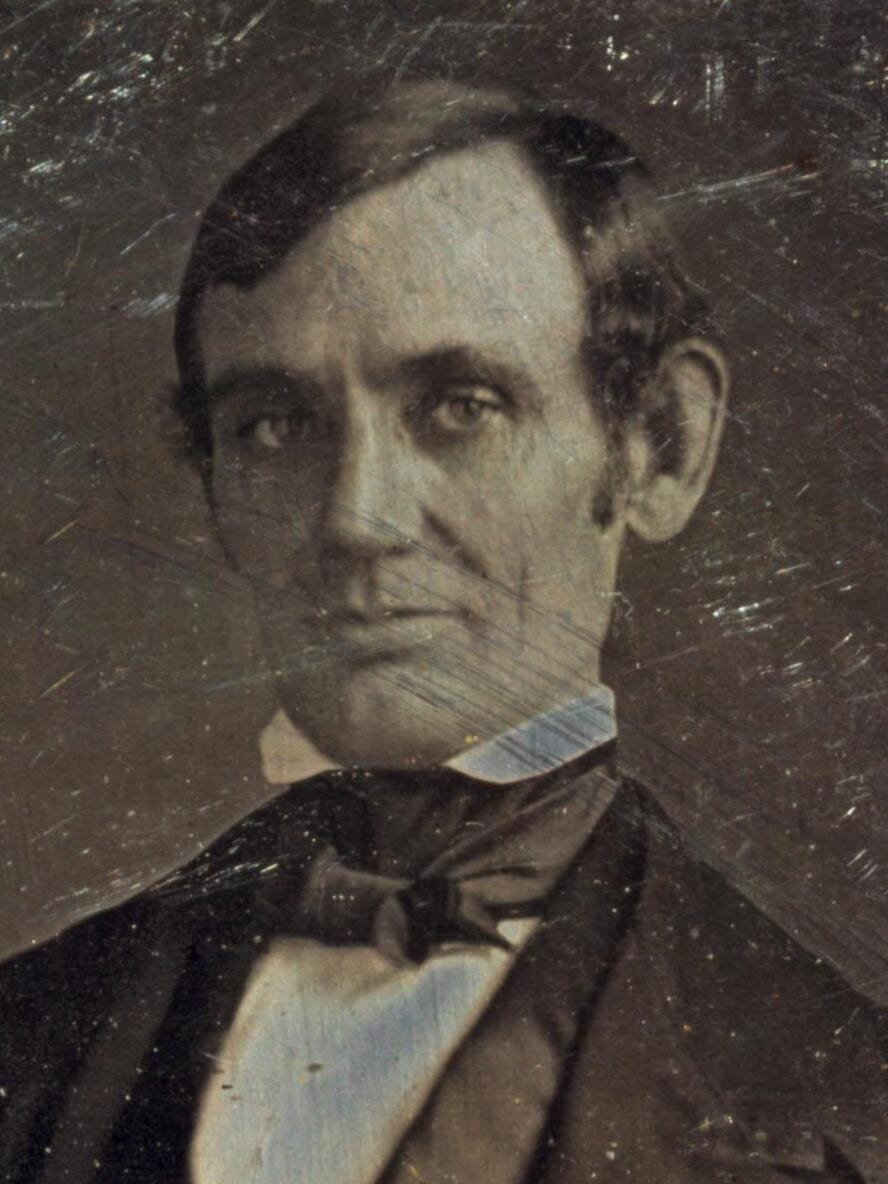

On January 27, 1838, Abraham Lincoln spoke to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois. His topic can be summed up in a sentence: “Outrages committed by mobs are the every-day news of the time.”

The 28-year-old Lincoln, a lawyer and state legislator, cited the outbreaks of violence that made him fear for the future of America’s experiment in self-government. There was a lot to be worried about.

In July, 1835, the citizens of Vicksburg, Mississippi hanged five people suspected of being professional gamblers. In April, 1836, a black man facing murder charges in St. Louis was seized by a white mob, chained to a tree and burned alive. Realizing the torture that awaited him, Francis McIntosh had begged in vain for someone to shoot him.

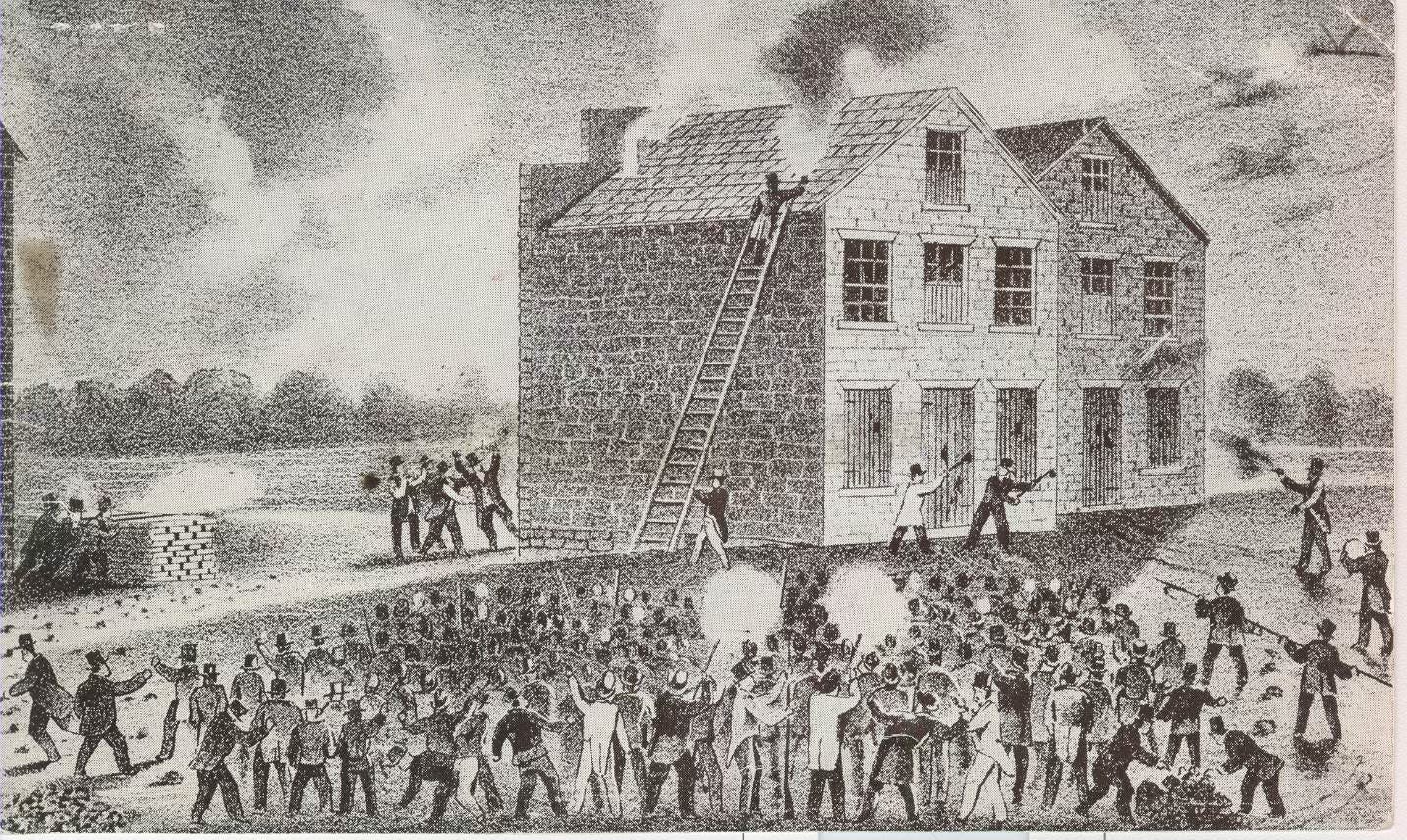

And a little more than two months before Lincoln spoke, an anti-slavery newspaper editor who was trying to defend his printing press from a mob was shot to death.

After editor Elijah Lovejoy died, the crowd chopped up the press and threw the pieces into the Mississippi River on the off-chance that some other journalist might use it to air arguments against slavery.

Lovejoy was murdered in Alton, Illinois, less than 90 miles south of Lincoln’s Springfield home.

No wonder Lincoln thought there was an “ill-omen” in America: “the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country; the growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgement of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive ministers of justice.”

The existential threat to the United States, Lincoln argued, didn’t come from overseas, from “some transatlantic military giant.”

It came from within. If the U.S. was to perish, it would be the result of its own internal conflicts. “If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher,” Lincoln said. “As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

Lincoln’s words, and Lovejoy’s life, are worth remembering today at a time when free expression is under assault. The Trump administration is seeking to regulate what the media can say while it also aims to scrub the nation’s memory of the wounds inflicted by slavery.

Mob violence

Ever since the killing of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, Americans have experienced political violence largely as a phenomenon of lone assassins, such as the man accused of murdering Charlie Kirk on a college campus in Utah or the one who fired a gun at then-former President Donald Trump in Butler, Pa. Of course, Lincoln himself fell victim to an assassin. So did Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in the nightmare year of 1968.

Yet there is an equally strong current of mob violence in American history — not least the events of January 6, 2021 — that goes back to the early years of the republic. One spasm of violence crested in the mid-1830s, during the populist administration of President Andrew Jackson and at a time of increasing activism against slavery.

“In the peak year of 1835,” wrote Daniel Walker Howe in his book: What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of American 1815-1848, “the seventy-nine southern mobs counted by historian David Grimsted killed sixty-three people, while the sixty-eight northern mobs killed eight.”

U.S. cities had no police forces in those days. But even cities that in later years did employ police, starting with New York City in 1844, experienced deadly mob violence, often aimed at Black citizens and communities.

Perhaps the most horrifying example is the May 31, 1931 attack on the Greenwood neighborhood in Tulsa, Okla. known as “Black Wall Street.” A lynch mob that falsely accused a black man of attacking a white woman set off a confrontation that completely destroyed the 35-block neighborhood, killed an estimated 175 to 300 people and left thousands homeless or imprisoned.

There were other incidents which could provoke mob violence: “The largest riots, surprisingly, were those directed against theaters where prominent British actors accused of anti-American remarks were performing,” Howe noted.

On May 10, 1849, thousands of fans of the American actor Edwin Forrest converged at the Astor Place Opera House in New York City. They were mostly working-class men who objected to the performance of William Macready, a British actor, in Macbeth. As the Folger Shakespeare Library recounted, Forrest and Macready “had been professional rivals, with increasing contempt for each other’s work and approach to the classic Shakespeare roles…Forrest was the hero of the working man and the lower classes; Macready was praised by wealthy Americans and literary opinion leaders.” The state militia fired on the unruly crowd and at least 22 people died.

Lovejoy

At 34, Elijah Parish Lovejoy was only six years older than Lincoln. But he had lived an eventful life, full of tense confrontations over press freedom.

Lovejoy was the kind of person who adopted a principle and stuck with it, no matter what. Born in rural Maine, he moved west as a young man and underwent a religious awakening. While he pursued a career as a newspaper editor, he also became a Presbyterian minister. Lovejoy shared the anti-Catholic prejudices of his co-religionists.

Like many critics of slavery in his day, he was at first put off by the intensity and relentlessness of abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison

But in time, he became a recruit to their cause, seeing slavery as a sin with which it was impossible to compromise. He cast off belief in the colonization movement, which sought to emancipate slaves only gradually and exile them to Africa.

Lovejoy believed steps should be taken immediately to end slavery. His religion-focused newspaper reflected that view, though he did make room in its columns for opposing arguments.

Defiance

The editor saw free expression as a fundamental right and promised he would never surrender it. “You may burn me at the stake, as they did McIntosh at St. Louis,” Elijah Lovejoy told a community meeting in Alton, “or you may tar and feather me, or throw me in the Mississippi, as you have often threatened to do. But you cannot disgrace me.”

The editor said his conscience impelled him to continue airing his views on slavery in his newspaper. “I am but one and you are many,” he said, as Ken Ellingwood recounted in his book First to Fall: Elijah Lovejoy and the Fight for a Free Press in the Age of Slavery. “You can crush me if you will; but I shall die at my post because I cannot and will not forsake it. Why should I flee from Alton? Is this not a free state?”

Alton was indeed in the free state of Illinois, but it was very near the slave state of Missouri. and many in its business community wanted to keep doing business with states to the south.

The citizens committee deliberating the fate of Lovejoy’s newspaper concluded that it shouldn’t be allowed to operate — and indeed that no newspaper advocating the abolition of slavery should be tolerated.

Alton had been Lovejoy’s refuge after threats of violence forced him to flee St. Louis and a mob wrecked his newspaper office there.

But his foes soon destroyed the printing press of his new newspaper, the Alton Observer.

As he made his case before the Alton citizens committee in November, 1837, Lovejoy was nervously awaiting the arrival of a replacement press. When it arrived, Lovejoy’s supporters managed to safely move the press from a river boat to a warehouse near the harbor. They, including Lovejoy, took up arms in the warehouse to defend the press and themselves from the oncoming mob.

Rocks were thrown; shots were fired. The rioters began trying to torch the building. Lovejoy and a friend stepped outside the warehouse to try to stop the members of the mob who were setting fire to the warehouse roof.

“Lead balls — five of them — tore into Lovejoy’s body before he had taken so much as a step,” Ellingwood wrote. Wounded in the chest, abdomen and left arm, Lovejoy exclaimed, “Oh, God, I am shot. I am shot.” Those were his last words.

A martyr

Lovejoy’s death galvanized opponents of slavery and supporters of press freedom. His story spoke of courage and principle. The journalist “insisted on delivering the Truth — capital T — as he saw it, on matters divine and secular,” observed Ellingwood. “Lovejoy was well aware that using a printing press to protest the enslavement of two million Black souls, even in the ostensibly free state of Illinois, was akin to putting a bull’s-eye on his back. He did it anyway.”

John Quincy Adams, the former president and now a serving member of Congress, compared Lovejoy’s murder to the shock of “an earthquake.”

Abraham Lincoln, referred to the killing in his Springfield Lyceum speech: “whenever the vicious portion of population shall be permitted to gather in bands of hundreds and thousands, and burn churches, ravage and rob provision-stores, throw printing presses into rivers, shoot editors, and hang and burn obnoxious persons at pleasure, and with impunity; depend on it, this Government cannot last.”

Remedy

In his Springfield speech, Lincoln tried to sketch out a way to quell the tide of mob violence:

The answer is simple. Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well wisher to his posterity, swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others. As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor; let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the character of his own, and his children's liberty.

Reverence for the law, Lincoln argued, should become the “political religion of the nation.” But just exhorting people to abide by every law and insist their neighbors do the same seems like an inadequate and unrealistic solution. It surely proved so in the tumultuous years that played out over the next several decades. And when Lincoln became president, he had to face the biggest violation of U.S. laws ever, in the form of the Confederate secession.

In his second inaugural speech, delivered a month before his assassination and shortly before Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln, then 56, spoke of the need to “bind up the nation’s wounds” and urged that the road ahead should be traveled “with malice toward none, with charity toward all.”

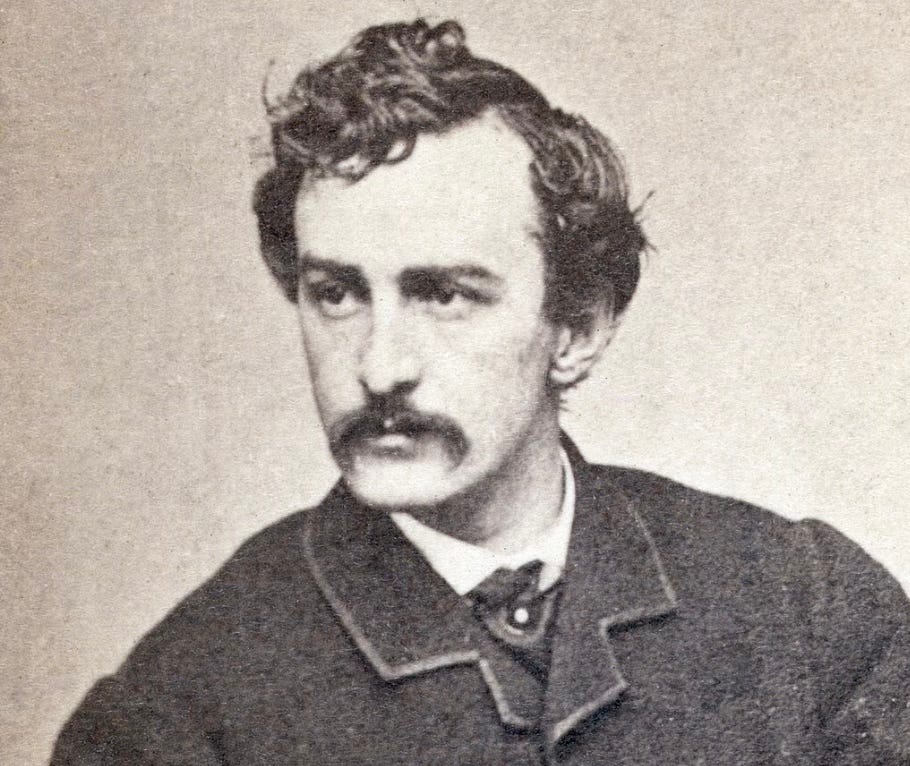

At Ford’s Theater

On April 14, 1865, President Lincoln and his wife Mary were watching the third act of “Our American Cousin,” a comedy, from a box at Ford’s Theater in Washington.

“John Wilkes Booth entered the unguarded box,” wrote Ronald C. White in his biography A. Lincoln. “He aimed a small derringer pistol at the back of Lincoln’s head, and, from a distance of six inches, fired one shot. Lincoln slumped ahead in his chair. Mary screamed in terror. [Major Henry] Rathbone rose to confront the intruder, but Booth, dagger in hand, slashed the young major before leaping from the box to the stage. He yelled in defiance, ‘Sic semper tyrannis!’ (‘Thus ever to tyrants.’)”

Some of those present said Booth, an actor who supported slavery and the Confederacy, also shouted, “The South is avenged.”

Unlike Elijah Lovejoy, Lincoln didn’t fall victim to mob violence. An assassin and his band of conspirators were guilty of the crime.

But both Lovejoy and Lincoln wound up dying as a consequence of America’s original sin of slavery.

A calm recollection for our troubled times. That early Lincoln Lyceum speech certainly seems prescient. (I tried the gimmick of using a long excerpt as an early "guest post" in my Substack, to limited effect.) Maybe because it is difficult to see clearly what surrounds you in the present, I don't see any one issue or any cluster of issues today that even comes close, objectively speaking, to the debate over slavery. Which seems pretty cut and dried, black and white (as it were) at least in retrospect. I'm trying to come up with a list as I write--the size of the permanent federal bureaucracy, trans rights, the hyper-vigilant policing of speech on college campuses, the place of immigrants, the hollowing out of our middle class amid deepening inquality...--each one and all perfectly valid matters for political debate and pragmatic policy responses. But not one, nor some or all of them considered together, justifies or explains the apparent depth of civil/political strife facing the United States today (at least to me). For that reason, the strife feels manufactured, the character of the debate deliberately inflamed, and out of all proportion with the objective circumstances. While there may never be an "objective correlative" for anything that happens in an irrational world, I still want to know why. Who does this benefit? I know enough to know that I don't know a lot. There are invisible forces afoot, including technology and monstrously big money. And it does feel like the pressure is building, and that the formal political structures may not be able to channel it effectively. (That point seems obvious). As I've learned through reading some history and serving as a political officer in certain countries that were going through wrenching transitions, the inflamed debate and unresolved pressure are likely to spill out into the streets and explode, as we are seeing here, into violence. Are these the early sparks of a coming conflagration? Or a warning light flashing red that we will respond to appropriately before it's too late? That is the question, not that I expect any answer other than what happens. Although the "die by suicide" phrase echoes in my mind and makes me queasy...