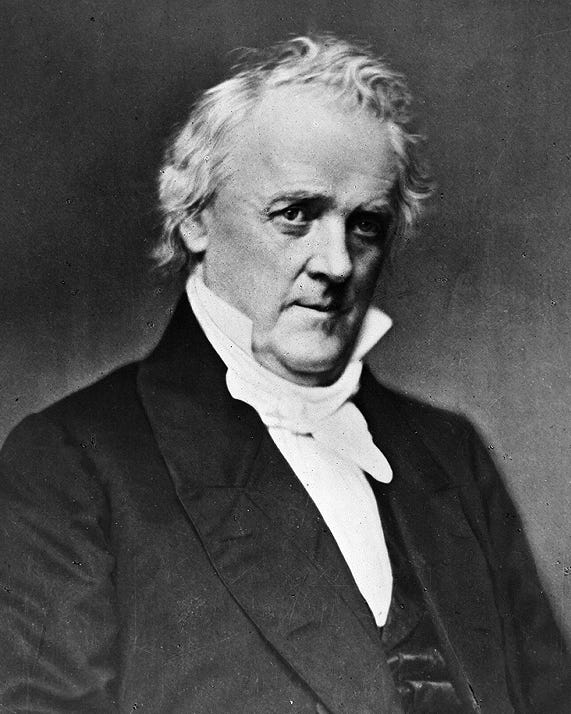

The president who failed — and the cabinet that abetted him

James Buchanan surrounded himself with yes-men

When Abraham Lincoln was elected president, he surprised his defeated rivals for the 1860 presidential nomination by giving them key positions in his cabinet.

“The powerful competitors who had originally disdained Lincoln,” wrote Doris Kearns Goodwin, “became colleagues who helped him steer the country through its darkest days.” The resulting “team of rivals,” to use Goodwin’s label, helped Lincoln earn the informal title of America’s greatest president.

It is striking that in the four years before Lincoln demonstrated how to be a supremely effective president, James Buchanan showed the nation the damage an incompetent one could wreak.

Buchanan began by choosing his cabinet unwisely. It tilted heavily toward the interests of the slave-holding South at a time when the potential dissolution of the Union was considered a real danger. By design, Buchanan’s cabinet echoed and supported his own views rather than challenged them. Instead of embracing his defeated rival for the Democratic nomination, Stephen Douglas, the president did his best to marginalize him.

Buchanan’s term as president became a four-year slide toward civil war. He is often ranked as the worst president in American history.

The lowest points of Donald Trump’s second term — killings on the streets of Minneapolis, retribution against perceived “enemies” and journalists, attacks on the rule of law, air strikes on small boats alleged to be carrying drugs — are not only the work of the president. He is being abetted by White House advisers like Stephen Miller and cabinet members such as Pam Bondi, Kristi Noem and Pete Hegseth.

A president has immense power, but must rely on subordinates to carry out his wishes. It is a lonely job, and so presidents need people who can wisely support them with advice and at times, warnings if they go too far. Yet many of Trump’s advisers are failing both the president and the nation by not standing up for the essential principles of American democracy.

The world was very different in 1857 when James Buchanan took office. But the damage that was done by a president and his overly submissive set of advisers bears a resemblance to the politics of 2026.

Well-prepared

When Buchanan took the oath of office, few people could have predicted the dismal outcome of his presidency. At least on paper, he was well-prepared for the White House.

The parallels between Buchanan and the career of a successful president — James Monroe — are striking. Both men got their start as small-town lawyers. They knew the ins and outs of government: they served as U.S. senators, as diplomatic representatives of the nation in Europe and as Secretary of State.

Both were intensely interested in expanding the borders of the young nation.

But while Buchanan surrounded himself with loyalists, Monroe reached out to a former member of the opposing Federalist Party, the able John Quincy Adams, to serve as his secretary of state. Together Monroe and Adams crafted the foreign policy doctrine we know as the Monroe Doctrine, which has been newly invoked by President Trump.

If there was one crucial difference between the careers of Monroe and Buchanan, it was this: James Monroe had the backing and mentorship of his gifted fellow Virginian planters Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, and for a time George Washington himself. Buchanan, on the other hand, served two presidents diligently — Andrew Jackson and James Polk — but was never able to gain their full trust or guidance.

Moving up

Like any self-respecting 19th century president, Buchanan was born in a log cabin. His birthplace was in the mountains of southern Pennsylvania, where his father owned a well-situated trading post in Cove Gap. James Buchanan Sr. named it “Stony Batter” after his family home in Northern Ireland, in County Donegal.

A graduate of Dickinson College, the young James Buchanan apprenticed as a lawyer and opened his own practice in Lancaster. As Jean H. Baker wrote in her biography of the 15th president, Buchanan became a “rising star” among the town’s lawyers, earning the present-day equivalent of more than $300,000 a year by the time he won election to Congress in 1821. (When he died in 1868, his estate amounted to $300,000, or more than $7 million today.)

The prosperous young lawyer seemed headed for a dream marriage to Ann Coleman, daughter of another emigrant from County Donegal, a mine owner who was Pennyslvania’s richest man. But the engagement soon broke up.

Jean Baker noted, “Ann informed her suitor that he did not treat her with sufficient attention or affection and that he was only interested in her money. As for Buchanan, his reasons may have involved sexual preference, for there has long been suspicion that our only bachelor president was a homosexual.”

There were rumors that after the breakup, Buchanan was courting another woman. Ann’s mother “rushed her off to recover in Philadelphia, where, inexplicably, this previously healthy twenty-three-year-old died suddenly of what one doctor diagnosed as ‘hysterical convulsions.’” Many believed that she died of an overdose of laudanum, either accidental or intentional.

“Thereafter Buchanan propagated the myth that he maintained his single status as a measure of devotion to ‘the only earthly object of my affections,’” Baker wrote. “In fact he informed a friend in 1833, when he was in his early forties, that he soon expected to wed.” He didn’t.

The southern connection

When Buchanan arrived in Washington, he began to associate not with fellow northerners but with his congressional colleagues from the South. As Baker pointed out,

Buchanan gravitated toward southerners and away from New Englanders, whom he considered radical extremists. As a bachelor with time on his hands, he found southerners more congenial both socially and ideologically. For a time he boarded with Senator William King of Alabama and ate in a southern “mess” on F Street. In the late 1830s, by then a senator, he lived in Mrs. Ironsides’s boardinghouse on Tenth near F Street, again with King. So intimate was he with the handsome Alabama senator, who was known as a dandy in his home state and an “Aunt Fancy” in Washington, that one congressman referred to the two men as “Buchanan & his wife” in a reference to their bachelor status, which also hinted at their homosexuality.

In Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King, historian Thomas J. Balcerski writes that “their nearly ten-year boardinghouse relationship appears quite unusual in retrospect,” given their many differences in background.

Still, Balcerski concluded, “the surviving evidence neither supports a definitive assessment of either man’s sexuality, nor the occurrence of a sexual liaison between them. Instead, this book argues that their relationship conformed to an observable pattern of intimate male friendships prevalent in the first half of the nineteenth century.”

William Rufus King served as a senator from Alabama and, briefly, as vice president of the U.S. in 1853, until his death from tuberculosis six weeks after taking office.

The lasting importance of the relationship was the influence of King and other southerners in helping shape Buchanan’s political views. As a member of Congress, the future president almost invariably sided with the south rather than his own northern region on the biggest national issues. He blamed northern abolitionists for the recurring crises over slavery.

“Buchanan became known as a ‘doughface,’ a man whose principles did not conform to those of his section, but rather were malleable like dough,” observed Baker. “He was a northern man who favored the South.”

Baker noted that Buchanan opposed slavery in theory but feared that the controversy over abolishing it would tear the Union apart. He wrongly believed that the abolitionist movement was ‘weak, powerless, and soon to be forgotten.’”

White House

Buchanan finally achieved his presidential ambition in the election of 1856, defeating John C. Frémont of the newly formed Republican Party and former president Millard Fillmore, the candidate of the American, or “Know-Nothing” party.

Yet everything almost came undone. On a pre-inauguration visit to Washington, the 65-year-old Buchanan “contracted a debilitating dysentery, called the National Hotel disease, which was the result of frozen pipes spilling fecal matter into the hotel’s kitchen and cooking water,” Baker noted.

Buchanan’s nephew, who was working as his secretary, died, along with other guests. “Buchanan survived but was intermittently afflicted for months with severe vomiting, cramps, and diarrhea. Even in March, during a periodic flare-up, he worried that he might faint or worse during his inaugural speech, and so a doctor sat in the front row, handy with brandy and smelling salts.”

Despite the president’s digestive concerns, the inauguration proceeded on a grand scale with a four-foot high cake, 1200 quarts of ice cream and $3,000 worth of wine. Buchanan’s stylish niece, Harriet Lane, served as his First Lady and earned a reputation as a gracious hostess.

In creating his inner circle, Buchanan wanted a “consensual cabinet that he anticipated would serve as a sounding board for his ideas…For a lonely man, its members must be friends, who would fill his days with conversation, share his dinners, and, as later transpired, when their wives were out of town, sleep in the White House.”

Baker added:

In the end Buchanan’s cabinet selections proved a disaster. To choose, as he did, four members from the future Confederacy and three northern Democrats who, like Buchanan, were doughfaces was an insult to the North. All four of the southerners had at one time or another been large slaveholders, and his special pet, Secretary of the Treasury Howell Cobb of Georgia, had once owned over one thousand slaves. All were wealthy men— aristocratic southern politicos whom he enjoyed entertaining in the White House.

The cabinet would meet for hours every afternoon except Sundays, with Buchanan as the dominant figure.

The invitations for post-cabinet dinner with the president “made for a pretty congealed and tight group,” wrote Robert Strauss, in his book Worst.President.Ever, “but it also meant no one was telling Buchanan when he went off kilter, as he was wont to do. He would often waffle on major issues, and could easily come up on the most ill-advised side of them.”

Before he took the oath of office as president, he secretly lobbied two members of the U.S. Supreme Court to issue a sweeping ruling about whether blacks could be considered slaves in U.S. territories. In his inaugural speech, he sought to minimize the issue by saying it was a judicial matter that would be “speedily and finally settled.”

To the forthcoming Supreme Court decision, he said, “in common with all good citizens, I shall cheerfully submit, whatever this may be.” Buchanan expected the ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford to take the question off the table for good.

The court’s infamous ruling found that African Americans could never be citizens of the United States. Rather than settle the question of slavery’s extent in the U.S., it inflamed the issue and triggered a wave of protest from among others, Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

Buchanan dealt ham-handedly with the conflicts between pro- and anti-slavery forces in Kansas. His effort to push through Congress the dubious Lecompton constitution that allowed slavery in the future state of Kansas prompted an investigation of his administration’s pressure tactics.

As Baker noted, while Buchanan “was too rich” to engage in personal corruption, “certainly his cabinet officers were among the most corrupt in American history. Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson sent agents to Kansas to further the administration’s interests, paying for them out of his department’s funds. Secretary of War John Floyd undersold Fort Snelling, an army post in Minnesota, to a consortium that included a fellow Virginia Democrat and friend. In other instances the War Department bought worthless carbines from favored companies, agreed to pay inflated prices for desired real estate necessary for its installations, and overpaid Democratic contractors.”

No criminal charges resulted “but many citizens were shocked at the amount of graft permeating all agencies and levels of the Buchanan government,” Baker wrote.

Several of Buchanan’s cabinet members went on to serve the Confederacy. Their careers are chronicled by the Miller Center:

Howell Cobb administered the oath of office to Confederate President Jefferson Davis and served as a brigadier general and major general in the Confederacy.

John Floyd also became a Confederate brigadier general, but was relieved of his post by Jefferson Davis after Floyd abandoned his troops.

Jacob Thompson was the luckiest of the three: the Confederacy gave him $200,000 plus proceeds from bank and train robberies in the north. He was supposed to use the money in his role as a confederate agent in Canada. When the civil war ended, Thompson fled to France, where he lived well in the Grand Hotel and refused to return the money. Ultimately, he came back to Mississippi but never faced prosecution.

His last crisis

Buchanan’s biggest presidential blunder was his final one — the complete failure to take action as states began to secede from the federal government. He thought secession was unconstitutional, but also believed that as president, he had no constitutional power to stop it.

Many historians argue that Buchanan was wrong. Among them is Baker, who wrote: “A vigorous reaction to the secession of South Carolina, indeed a strong response to the taking of federal property throughout the cotton states, would have stanched the departure of others.”

Her verdict on Buchanan is devastating:

He was that most dangerous of chief executives, a stubborn, mistaken ideologue whose principles held no room for compromise. His experience in government had only rendered him too self-confident to consider other views. In his betrayal of the national trust, Buchanan came closer to committing treason than any other president in American history.but also opposed any action that might have prevented it.

Seven of the 11 states that formed the Confederacy seceded under Buchanan.

On the day of Lincoln’s inauguration, the outgoing president rode in a carriage with his successor and said, “My dear sir, if you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man indeed.”

But at his retirement home in Lancaster Township, Pennsylvania, Buchanan couldn’t rid himself of his outrage at being blamed for the civil war. Atttempting to restore his reputation, he wrote a book, the first published presidential memoir: Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion.

He again castigated the abolitionists. “The original and conspiring causes of all our future troubles are to be found in the long, active and persistent hostility of the Northern Abolitionists, both in and out of Congress, against Southern slavery, until the final triumph of their cause in the election of President Lincoln; and on the other hand, the corresponding antagonism and violence with which the advocates of slavery resisted these efforts…”

Guess who Buchanan leaves off the hook:

“Mr. Buchanan never failed,” the former president wrote about himself in the third person, “upon all suitable occasions, to warn his countrymen of the approaching danger, and to advise them of the proper means to avert it.”

Good to know the incumbent never failed, that everything he did was for the good and at any rate could not be avoided, and that whatever problems may have occurred at the time were entirely the fault of other people. Could it be that figures dominant in their era will be remembered differently in subsequent eras, less charitably, depending? And can we expect that a truly terrible president surrounded by far worse than yes men might be succeeded by a wise leader equal to the moment who rises to the historical occasion to save the day and the nation again? I know we can't know the future, and I don't subscribe to the "great man" theory of history, but if anyone has seen the finale of season 2, pray tell.

Terrific historical deep dive. The Lincoln vs Buchanan cabinet comparison really drives home why surrounding yourself with yes-men is dangerous in executive leadership. What really stood out to me is how Buchanan's southern-leaning appointees essentially guarenteed the admin would fail to address secession decisively. I once studied similar leadership failures in other contexts and the pattern of avoiding dissenting voices always ends badly.