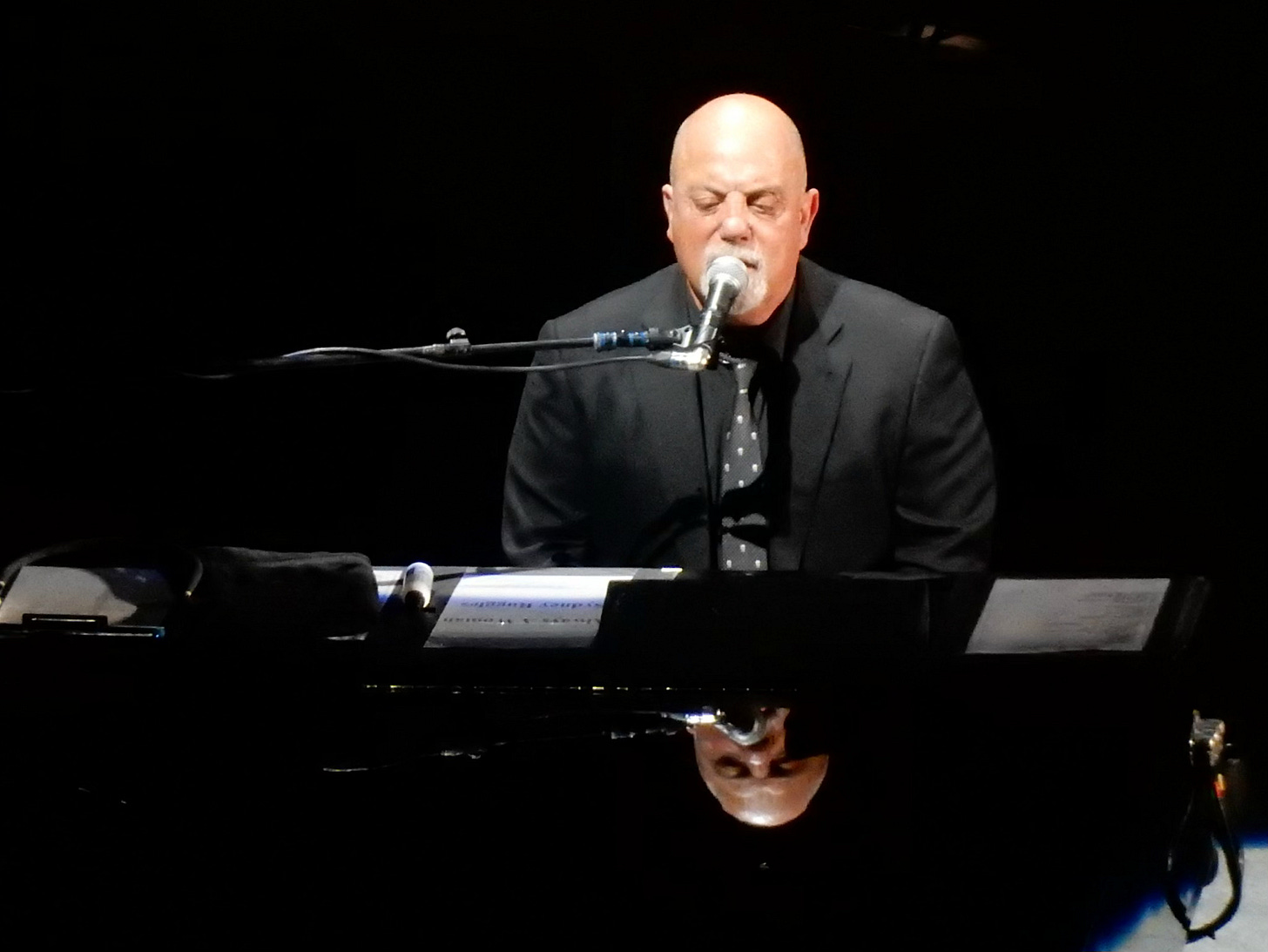

The song that explains Billy Joel

A ballad from a real time and place

When Nick Paumgarten profiled Billy Joel for The New Yorker in 2014, the article was headlined: “Thirty-Three-Hit Wonder.”

Those words captured Joel’s position in pop culture: astounding popularity, with scant critical respect. His 33 Top 40 hits are “about twice as many as Springsteen, the Eagles, or Fleetwood Mac,” Paumgarten noted.

Most songwriters would kill to have just one Piano Man or Movin’ Out. But for decades, critics looked down on Joel: Dave Marsh called his work “Self-dramatizing kitsch” and, to Robert Christgau, he was “a force of nature and bad taste.”

But there was another sense in which the headline’s play on “one-hit wonder” seemed right. Billy Joel essentially stopped writing songs in 1993, with some minor exceptions. In the years since, he wrote music in a classical vein and toured occasionally. His jukebox was frozen in time, with no promise of more lyrics to come. He began to look like someone who was lucky enough to catch a…