Trouble in Trump country

A magic bean is giving his team indigestion

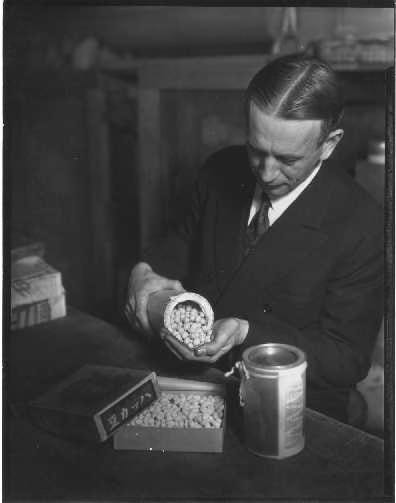

In June, 1907, a tall young man named William F. Morse reported for his first day of work at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The 24-year-old, a former high school football player in his hometown of Lowville, N.Y., had just graduated from Cornell University. He was assigned to Charles Vancouver Piper, who headed the USDA’s office of forage crops.

Piper thought soybeans, which were barely grown in America, held immense potential for the nation’s farmers. So he put Morse to work growing soybean varieties on an experimental farm in Arlington, Virginia, which is now part of the site of the Pentagon.

Soybeans took over Morse’s life and shaped his long career. He and Piper would write an influential 300-page book, The Soybean, published in 1923. Morse would help found the American Soybean Association and serve …