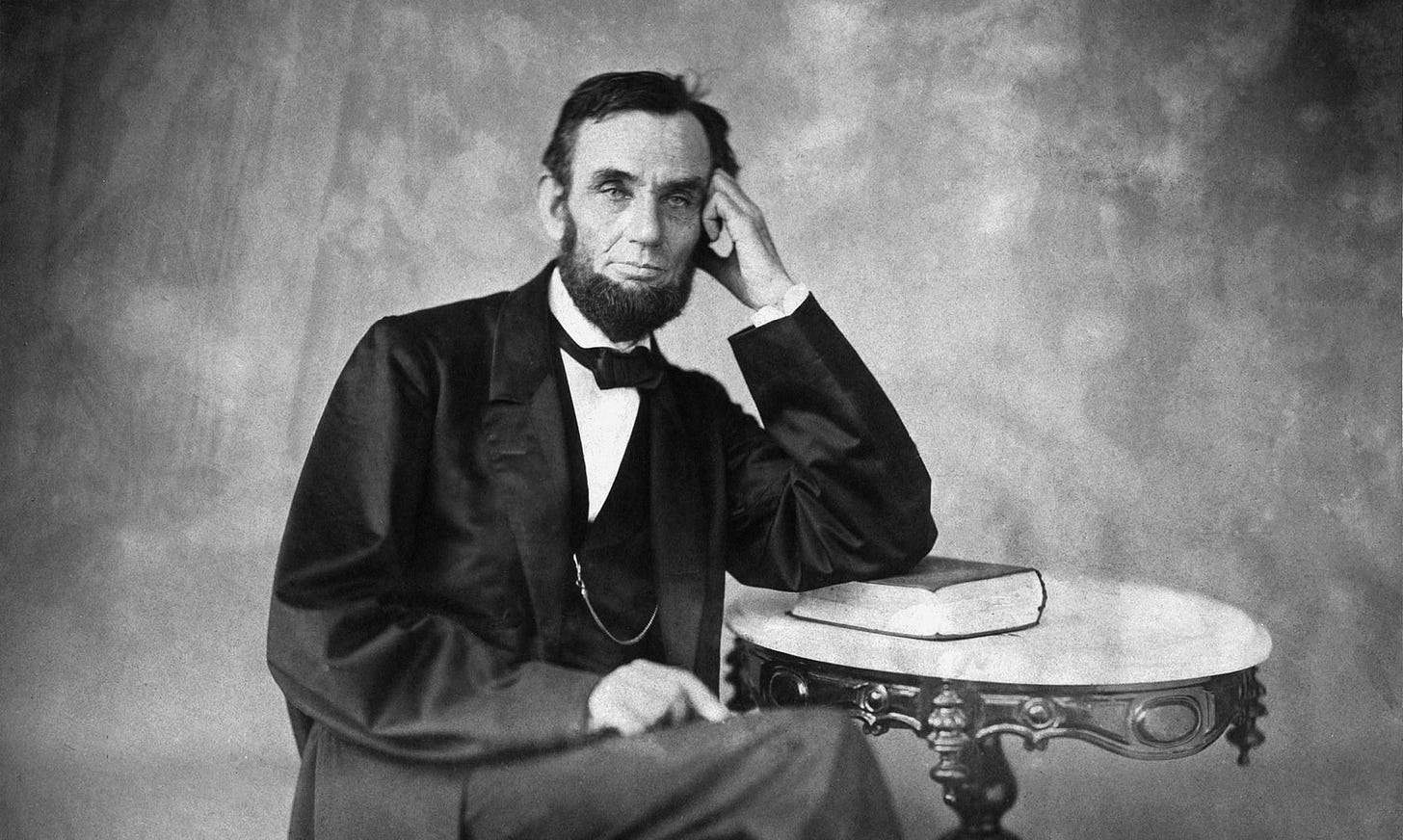

What Lincoln would tell Trump

About the president's deranged Rob Reiner post

At dusk on November 18, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln arrived by train at Gettysburg, the site of the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. Huge crowds had gathered at the home of lawyer David Wills, who was hosting the president. Lincoln told the Pennsylvanians that he had no speech to make that night.

“In my position it is somewhat important that I should not say any foolish things.”

Someone cried out, “If you can help it.”

Lincoln replied, to laughter, “It very often happens that the only way to help it is to say nothing at all. Believing that is my present condition this evening, I must beg of you to excuse me from addressing you further.”

The next day, on the battlefield where more than 50,000 soldiers had been killed or wounded four months earlier, Lincoln did have a speech, a mere 272 words commemorating the battle and dedicating the cemetery.

“We cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow — this ground,” Lincoln sai…