What's driving the gold frenzy

The buying spree is sending a message

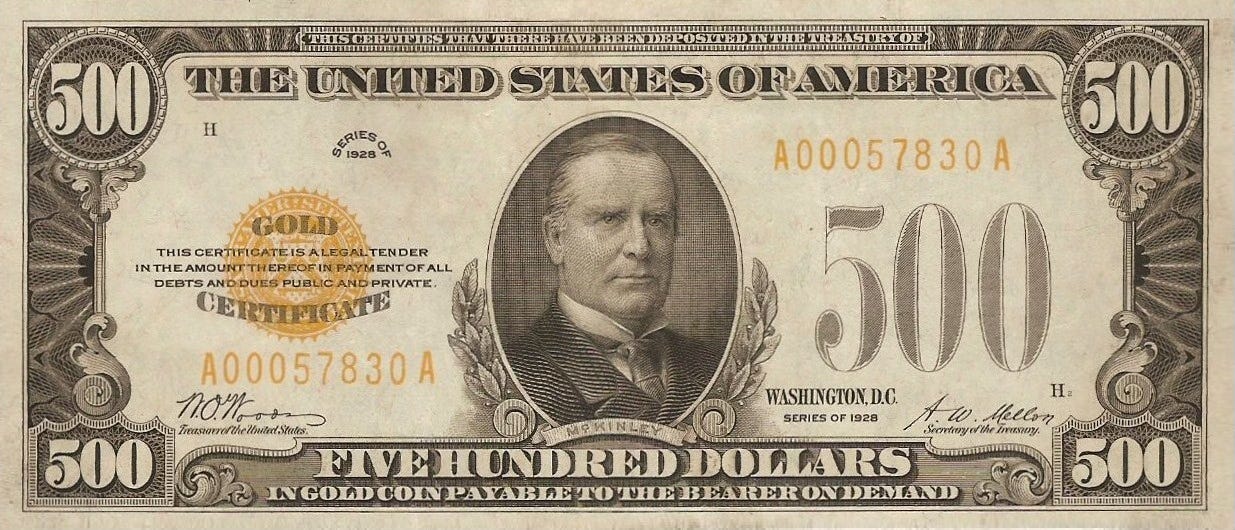

The villain played by Jeremy Irons in the 1995 thriller Die Hard with a Vengeance barks orders in a stilted German accent to gangmates who bomb a subway station and use a tunnel-boring machine to break through to the nearby New York Federal Reserve Bank’s gold vault.

“One hundred and forty billion dollars!” Irons’ character, Simon Gruber, gushes as he surveys the thousands of neatly stacked gold bars he is stealing. “Ten times what is in Kentucky.”

“Fort Knox, ha, is for tourists!”

The movie is pure fiction; the part about the size of the Fed’s New York gold stash isn’t.

It is indeed a larger horde of gold than Fort Knox, and by the current market price, the amount stored at 33 Liberty Street in lower Manhattan is worth more than $800 billion.

Gold on the bedrock

At its opening in 1924, The New York Fed was the largest bank building in the world. The architect, Philip Sawyer, harked back to his student travels in Italy when he replicated a Florentine palazzo, but on a much grander scale. He specified the use of contrasting-colored stones — limestone from Indiana and sandstone from Ohio — to lighten the effect of the 22-story building’s massive façade.

From the beginning, the building had a unique feature: Buried 80 feet below ground is a massive vault that holds nearly a quarter of the world’s gold supply.

You and I can’t store gold there. It’s only open to the U.S. and foreign governments, other central banks and international organizations. Last year, the Fed had custody of 6,122 metric tons of gold, an enormous weight that rests on the bedrock of New York’s Manhattan island.

Gold’s value has been on a wild ride. It’s up more than 50% so far this year, exceeding $4,000 an ounce for the first time. By contrast, the S&P 500 stock index is up 13.5% this year. Bitcoin, once touted as digital gold, crashed a week ago when President Donald Trump spoke about renewed trade tensions with China. About $600 billion in bitcoin value has been lost since then.

What’s driving the extraordinary rise in gold over the past two years? And can it last?

Some investment advisers recommend that people add a small position in gold to their portfolios. But there are noted skeptics, including Warren Buffett, who once said, “The idea of digging something up out of the ground, you know, in South Africa or someplace and then transporting it to the United States and putting [it] into the ground, you know, in the Federal Reserve of New York, does not strike me as a terrific asset.”

Gold is essentially an investment in fear, Buffett noted on CNBC in 2011. “But you really have to hope people become more afraid…than they are now. And if they become more afraid you make money, if they become less afraid you lose money. But the gold itself doesn’t produce anything.”

As Jessica Dickler of CNBC noted on October 8, citing data from the Morningstar research firm, stocks have proven to be a far better investment than gold in the past three decades. On average stocks have returned 10.7% a year since October 1, 1995. Gold has returned 8% per year. Stocks can pay dividends and company earnings can grow, increasing their value. Gold just sits there.

The Fed factor

It’s no accident that gold has zoomed upward during the first year of Trump’s second presidency. He’s waged war on Fed President Jerome Powell, demanding that interest rates be cut drastically, and has made a series of moves to weaken the central bank’s independence from politics.

Powell’s term as Fed chairman ends next May, and Trump is almost certain to replace him with a loyalist who will feel pressure to give the president the ultra-low interest rates he wants. The net effect: a weaker dollar, a faster-growing economy that becomes more reliant on debt and the risk of runaway inflation that will erode the dollar further.

Even before the end of Powell’s term, the Fed is prioritizing interest-rate cuts to help an ailing job market. It was Powell’s August 22 speech at the Jackson Hole symposium that set off the latest gold price spike.

Part of the run-up in gold values is being attributed to purchases by overseas central banks diversifying away from the dollar and other currencies whose countries are weighed down with heavy levels of government debt.

As the Economist pointed out: “Gross public debt as a share of GDP in advanced economies stands near 110%, close to an all-time high.” If a nation faces a debt crisis, lowering interest rates can juice inflation to lessen the burden of its borrowing. That is a way to pay off the debts with a devalued currency.

But former central banker Willem Buiter, who served on the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee, wrote in the Financial Times that, “The world is a thoughtless prisoner of history when it treats gold as a store of value, particularly central banks, which have seriously increased their holdings of gold since 2022…There will be no resurrection of the gold standard. Individuals and investment firms considering investing in gold should do so only if you can afford to lose most or all of this investment.”

Governments intervene

The often-cited appeal of gold is that its value is insulated from the actions of governments. They have great discretion in how much money they print and how much they spend, but very limited influence on how much gold is mined. Still, policy makers have intervened in the gold market several times in the past century.

Amid a banking crisis in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order on April 5 banning the “hoarding” of gold coins or bullion (above $100 in value per person) and giving Americans until May 1 of that year to turn in their gold to the Federal Reserve Bank.

“Many gold owners were understandably unhappy about the gold seizure, and some fought it in the courts,” wrote Chris Colvin and Phillip Fliers, in an article for The Conversation. “Ultimately, however, the government could not be stopped, and gold ownership remained illegal in the US until the 1970s.”

“This intervention was not unique,” Colvin and Fliers noted, citing restraints on gold ownership imposed by Australia in 1959 and the UK in 1966.

On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon shocked the world with a speech announcing a new economic plan his team had hashed out in secret talks at Camp David. In addition to freezing prices and wages for 90 days, cutting federal employment, decreasing foreign aid, reducing taxes and imposing a temporary 10 % tariff on all imports, he suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold.

The gold standard was suddenly gone. Investors in gold are probably safer from government intervention now. “But the one lesson from history that all investors need to bear in mind,” wrote Colvin and Fliers, “is that in times of crisis, anything goes.”

In the late 1970s, the price of gold doubled, just as it has in the past two years. As James Mackintosh noted this week in the Wall Street Journal, the pullback from the precious metal was fierce when the Federal Reserve radically shifted its interest rate policy.

“Gold halved in value in two years at the start of the 1980s as the Fed gave priority to tackling inflation despite a double-dip recession,” wrote Mackintosh.

“It took gold more than a quarter of a century to recover to its January 1980 peak, and after adjusting for inflation only regained its peak earlier this year. So much for gold having long-run stable value.”

Spoiler alert: Bruce Willis stopped Jeremy Irons from escaping with the New York Fed’s gold bars.

Is gold a better barometer of the underlying fear than the stock market is? I have been surprised that money, cowardly as it is, has continued to flock to the froth of stocks etc. Or is the coming collapse a matter of time? Unanswerable questions, I know.