When a city made America healthier

The blessing of clean water

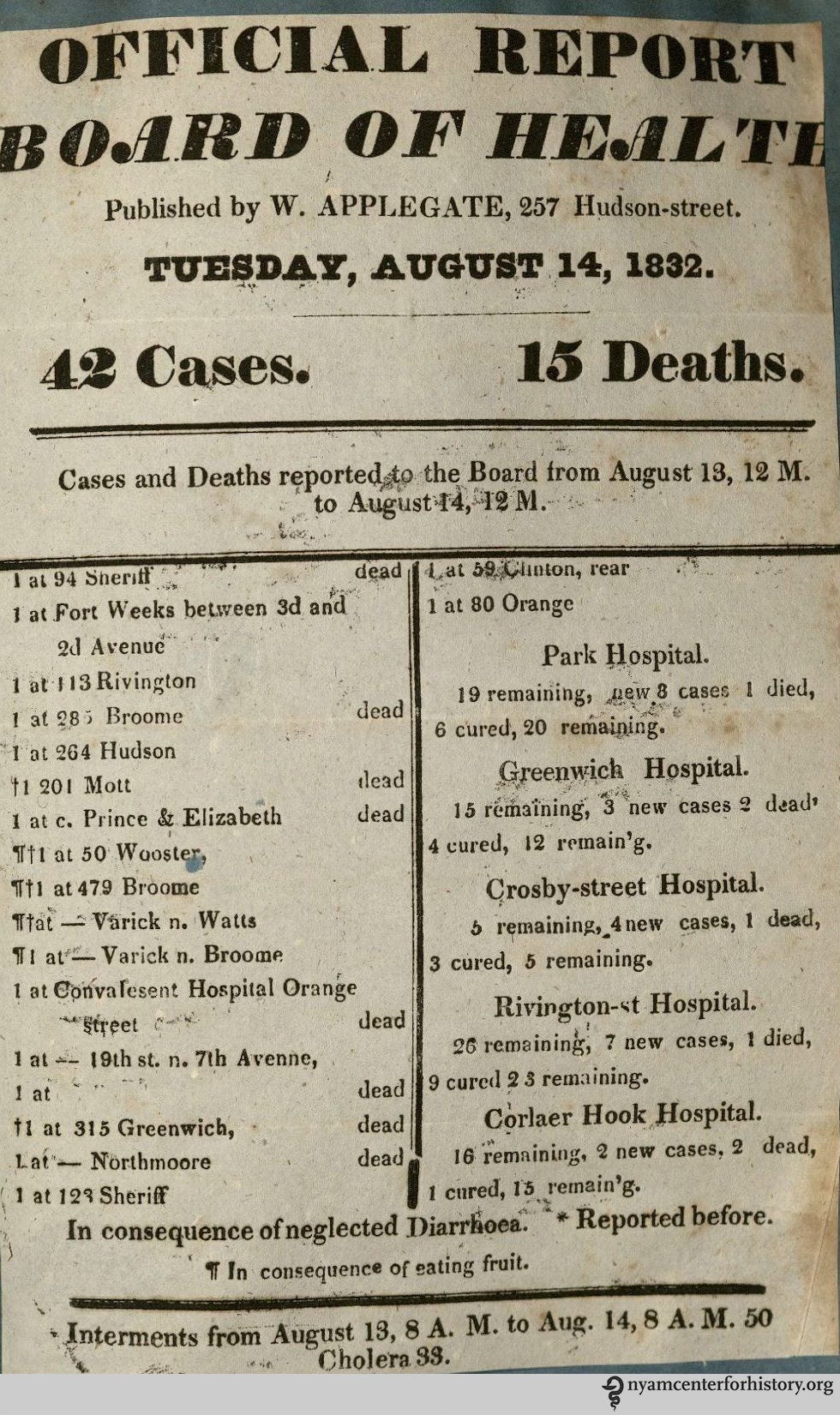

When a cholera epidemic struck New York City in 1832, tens of thousands of people fled.

Most of those who could leave decamped to houses in the countryside. Those left behind were the poor, many of them immigrants, trapped in cramped neighborhoods where disease spread more quickly.

“Cholera is an unnerving disease,” Charles E Rosenberg wrote in a 1959 article for the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, “its symptoms revolting, its prognosis discouraging, its etiology an indictment of the society which harbors it; a grim reminder of man’s mortality, it could not be ignored, or treated, or prayed away.”

Victims of severe cholera suffer from watery diarrhea, vomiting and leg cramps. The resulting dehydration can kill a person in just a few hours.

As Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace wrote in Gotham, their history of the city, “3,513 died, most of them horribly, the lucky ones swiftly. The young editor Henry Dana Ward wrote his parents that some ‘are taken like lightning from the midst of their families and daily work.’ One paper reported smugly that a prostitute who had been adorning herself before her glass at one was in a hearse by half past three.”

A prominent New Yorker, John Pintard, took comfort that the disease appeared to be “almost exclusively confined to the lower classes of intemperate, dissolute and filthy people huddled together like swine in their polluted habitations.”

No one knew then that cholera was caused by a bacillus or how it was spread.

Revisiting the story of the 1832 epidemic and its aftermath can shed light on how to promote health and fight disease. In the process, we will meet a remarkable artist who is only now getting her due recognition.

It’s a timely topic given the campaign by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to “Make America Healthy Again.” RFK is already undermining his project by weakening federal support for vaccines. In addition, the administration is gutting federal rules mandating cleaner air and water.

‘Water! Water!’

In 1832, while some wealthy New Yorkers were quick to blame cholera on supposed immorality among immigrants and the poor, the disease soon claimed victims who were well-to-do.

Far-fetched theories proliferated: As Rosenberg noted, “indiscretions in drink and diet were regarded as the most important predisposing causes: a pineapple or a melon was a death warrant, a dozen oysters, suicide, overindulgence in alcohol, the most dangerous of all.”

New York’s cholera epidemic ended within a few months, but the ordeal left the city reeling and still unsure what caused it. “On one thing,” Burrows and Wallace noted, “there was general agreement: New York City needed fresh, clean water. Even those who saw divine intervention at work didn’t contest physicians and sanitarians like William MacNeven and John Griscom who pointed to the polluted drinking supply and the poisonous vapors rising from the streets as major contributors to the plague.”

Concern over health — and providing a reliable means to fight fires — led the city to construct a massive 41-mile aqueduct system piping clean water from the Croton River in Westchester to Manhattan. The city employed about 4,000 workers and spent $13 million on the project.

When the water began to flow in 1842, New York threw itself a party: a five-mile-long parade, accompanied by ringing church bells and a hundred gun salute. “Nothing is talked of or thought of in New York but Croton water,” wrote one resident quoted by Burrows and Wallace. “Water! water! is the universal note which is sounded through every part of the city, and infuses joy and exultation into the masses.”

There were more cholera outbreaks, in 1849, 1854 and 1866, but the city was on course to improve public health.

A vital clue to conquering the disease came in 1854, when cholera struck London’s Soho neighborhood. John Snow, a doctor, began to map the locations of the disease’s victims. He “noted that they were mostly people whose nearest access to water was the Broad Street pump.” The local government removed the pump’s handle, limiting the disease’s spread. It turned out that the well’s water was being polluted by sewage from a cesspool.

The Angel

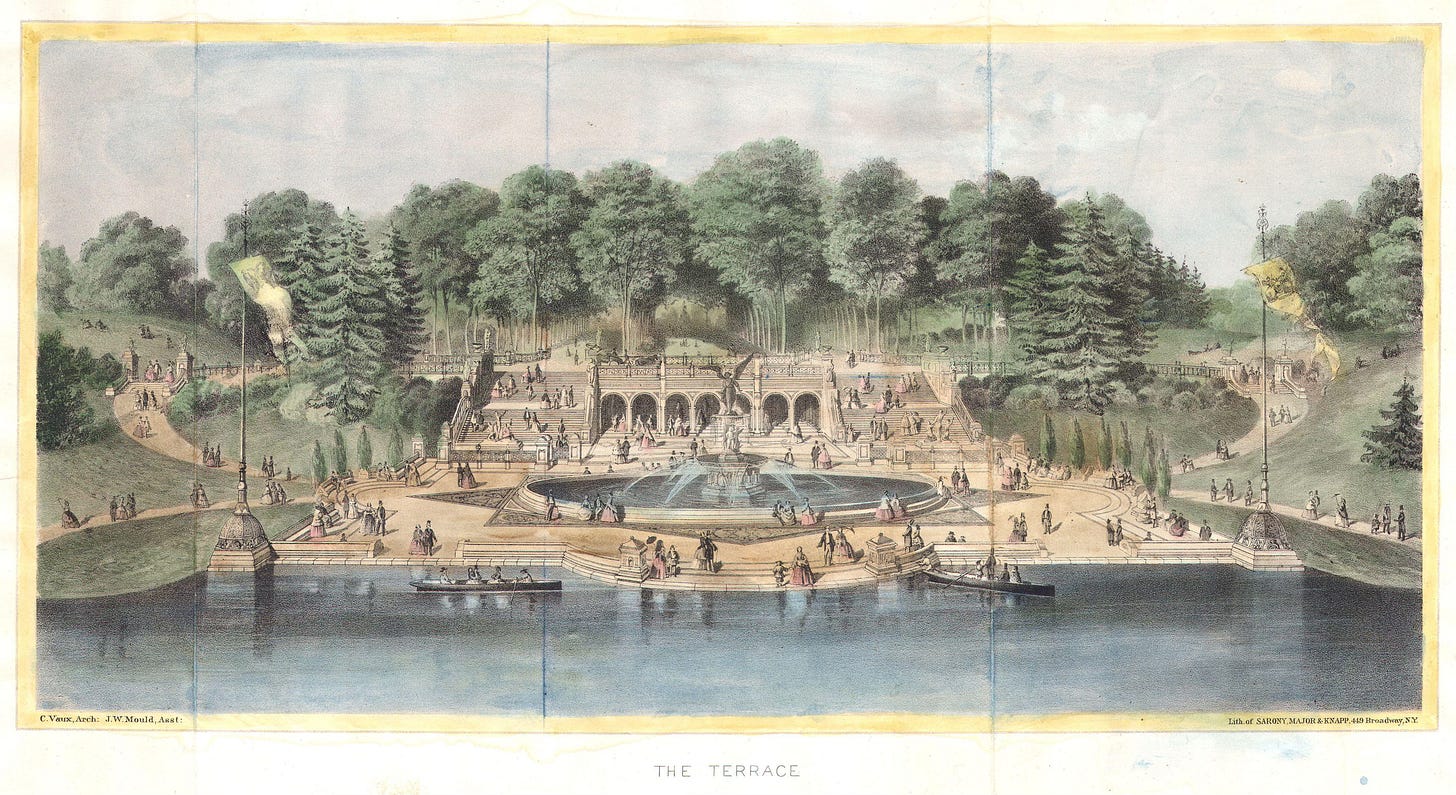

Thirty years after the arrival of Croton water, it was still a matter of pride for New York. By 1873, visitors to Central Park could congregate on a spacious plaza around a 26-foot-high fountain under the sheltering wings of the bronze “Angel of the Waters.”.

The Bethesda Fountain, at the heart of Central Park, is named after an ancient pool in Jerusalem. According to the gospel of St. John, the pool of Bethesda was visited by an angel who imbued the water with the power to heal.

Emma Stebbins, the artist who sculpted the Angel of the Waters had a very personal reason to take on the project: her father and her brother had died of cholera in the 1830s.

When New York’s sculpture was dedicated on May 31, 1873, Stebbins wrote in the event program that the figure of an angel seems an appropriate way to give thanks for “the blessed gift of pure and wholesome water, which to all the countless homes of this great city, comes like an angel visitant, not at stated seasons only, but day by day…”

That the cholera epidemic made a deep impression on Stebbins is made clear by “Carving Out History,” a new exhibition of her work at the Heckscher Museum in Huntington on Long Island. It includes a marble bust she sculpted in tribute to her brother John Wilson Stebbins, a victim of cholera.

How Emma was chosen for the Central Park project isn’t known. Another one of her brothers, Henry Stebbins, was a powerful force in New York at the time. In a long career, he served as president of the New York Stock Exchange, member of Congress, parks commissioner, president of the Atlantic & Great Western Railway, commodore of the New York Yacht Club and president of the New York Philharmonic.

He also served as a commissioner of Central Park when the statue was greenlit. But however Emma Stebbins was selected for the job, she vindicated the choice with a sculpture that draws attention from the millions of visitors to the Bethesda Terrace and Fountain every year. It has been featured in theater and in films including Elf, Enchanted and Annie Hall.

Stebbins was the first woman commissioned to create a large public works project for New York City. She designed it in Rome over a four-year period.

Safeguarding water

Scientists in Stebbins’ day didn’t have the same tools and knowledge we have to assess health risks. It’s clear now that cholera is far from the only disease spread by polluted water. The World Heath Organization (WHO) says diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid and polio are linked to contaminated water and poor sanitation.

There are other risks associated with drinking water. “Inadequate management of urban, industrial and agricultural wastewater means the drinking-water of hundreds of millions of people is dangerously contaminated or chemically polluted,” according to WHO.

A major concern is “forever chemicals”: PFAS (which stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances). They are materials used in consumer products that break down slowly and have been found in human and animal blood, as well as in food products. The EPA says that “PFAS are found in water, air, fish, and soil at locations across the nation and the globe” and that “scientific studies have shown that exposure to some PFAS in the environment may be linked to harmful health effects in humans and animals.”

The “first-ever standards for PFAS in drinking water were established by EPA under President Biden last year,” wrote Darya Minovi of the Union of Concerned Scientists on September 22. The Make America Healthy Again agenda makes a nod to the issue of forever chemicals, but in May, “the administration announced it would weaken those very standards. And just this week, the administration asked a court to eliminate all but two of these protections.”

“However the administration may address other parts of the strategy, when it comes to addressing ‘chemical exposure,’ it’s smoke and mirrors,” Minovi observed. “In reality, this administration is just bluntly increasing the risks of chemical exposure.”

To Rome

For Henry Stebbins, the son of a banker and one of nine children, a career in finance and politics was an obvious step. For his sister, Emma, the attitudes of the day confined her to few choices, and she chose fine arts.

In 1846, she traveled to Rome, where an active community of expatriate artists welcomed her. Emma soon met and fell in love with an actress, Charlotte Cushman, and they became partners for life.

“Strong, decisive, passionate, a shrewd steward of her own image and financial fortune, Charlotte was also generous to her expatriate artist women friends in Rome,” wrote Stebbins’ biographer Maria Teresa Cometto. “She hosted them, helped them, promoted them within the art world, and defended them from the envy and attacks of male competitors.”

Cometto told interviewer Jeanne Gutierrez of the New York Historical that Stebbins was “very shy and reserved.”

Describing herself, she observed: “(I am) a soft-shelled crab, forced by circumstances into hard-shelled positions.”

Cometto added, “She destroyed the letters she exchanged with Charlotte [Cushman] because Charlotte had asked her to: they were too scandalous and would have compromised the image of Charlotte herself, the very famous actress happy to be remembered as a ‘virgin queen of the dramatic stage,’ as the New York Times wrote in her obituary.”

In a 2019 piece, the Times noted that Cushman and Stebbins “gave lavish dinner parties and waffle breakfasts for the group at their home, and were known to wear black bowler hats and ride their horses to the Villa Borghese for picnics of red wine and cheese.”

“They eventually exchanged unofficial vows. Cushman described herself as married to Stebbins, telling a friend in an 1858 letter that she wore ‘the badge upon the finger of my left hand.’”

The relationship gave Stebbins another reason to reflect on the connection between health and water. When Cushman developed breast cancer in 1869, she tried “water cures at Malverne in England, as they were traditionally believed to be the treatment for reducing the disease,” wrote Sarah Cedar Miller in Central Park: An American Masterpiece. Cushman ultimately underwent surgery, and she survived until 1876. The couple had returned to the United States six years earlier.

Perfectionism

Stebbins took more of an activist role in her sculpture than many other artists, noted Cometto. “They employed Italian craftsmen to rough out marble blocks based on their models and then engaged with the chisel only in the final stage of statue creation…In contrast, Emma did everything herself, with maniacal perfectionism. It was a matter of professional pride and a desire to be independent, to maintain control of her work, without interference.”

“So Emma limited much of her production to small statues and didn’t make many copies of her statues,” noted Cometto. “But the hours and hours spent using hammer and chisel on marble, breathing in the dust, were harmful to the lungs and eventually proved fatal to Emma.”

Stebbins’ perfectionism helps explain why four years elapsed before her clay and plaster models of the Angel were ready for casting at a foundry in Munich. The Franco-Prussian War delayed the work for two more years. So when “Angel” was finally unveiled at the Bethesda Terrace in 1873, it appeared 10 years after the original commission.

While angels are traditionally represented as male, Stebbins sculpted hers as a woman. A New York Times writer panned it, comparing the rear view of the angel to “a servant girl executing a polka” and the front to a “a naughty girl jumping over stepping-stones…The head is distinctly a male head, of a classical commonplace, meaningless beauty, the breasts are feminine, the rest of the body is in part male and in part female.”

But that was not a universal view. Many others have appreciated Stebbins’ work and gotten the message about health and water that she was seeking to convey.

As the artist wrote in 1873, the angel “bears in her left hand a bunch of lilies, emblems of purity…She seems to hover over, as if just alighting on a mass of rock, from which the water gushes in a natural manner, falling over the edge of the upper basin, slightly veiling, but not concealing four smaller figures, emblematic of the blessings of Temperance, Purity, Health and Peace.”

In Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America,” the focus is on another plague that struck New York: AIDS. Like cholera, it was a health threat that science has helped to subdue. But both diseases still claim victims — and require the attention of a robust public health apparatus, one that appears to be in eclipse under the Trump administration.

In Kushner’s epilogue, a “heavily bundled” Prior Walter is sitting with some friends on the rim of the Bethesda Fountain on a bright, cold day. “This is my favorite place in New York City,” he says. “No, in the whole universe. The parts of it I have seen.”

He has been living with AIDS for five years.

“This angel. She’s my favorite angel. I like them best when they’re statuary. They commemorate death but they suggest a world without dying. They are made of the heaviest things on earth, stone and iron, they weigh tons but they’re winged, they are engines and instruments of flight. This is the angel Bethesda.”