Words Donald Trump will never say

The pivotal role of the concession

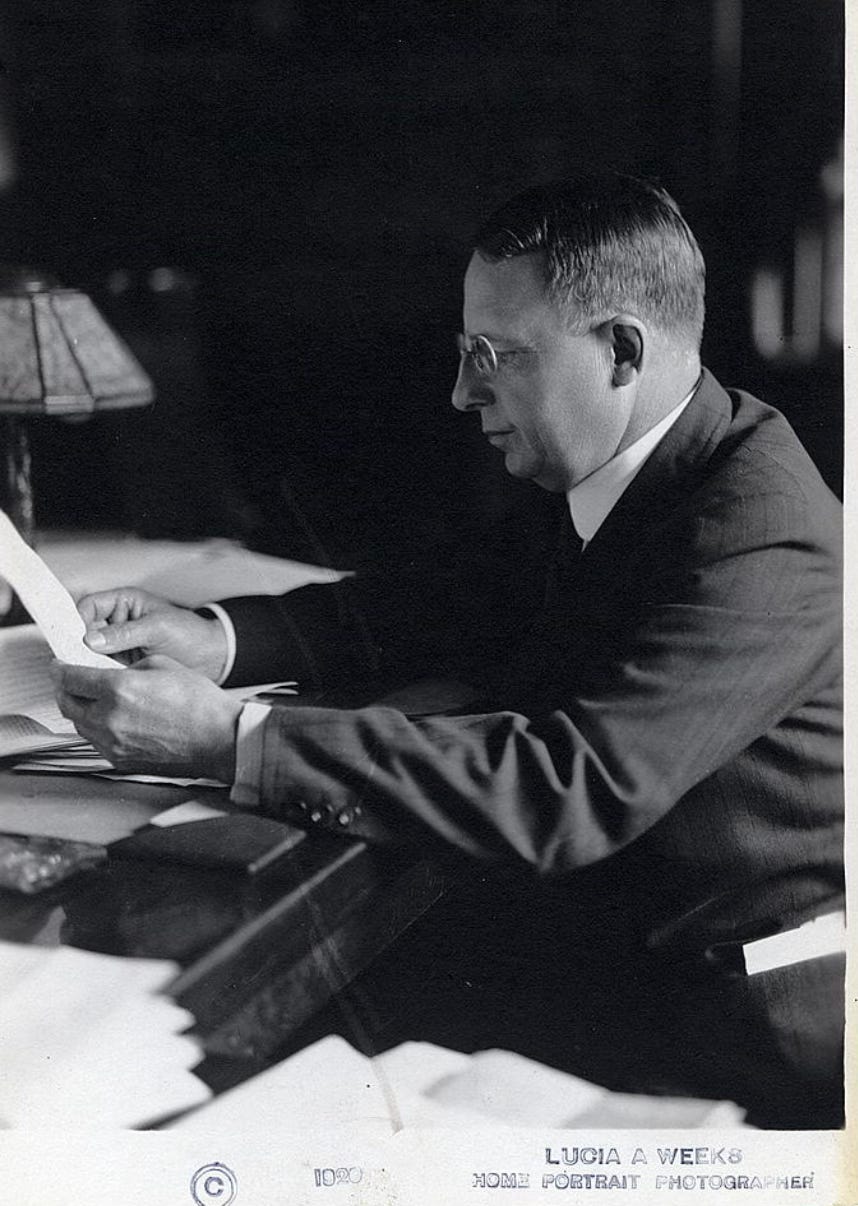

On November 3, 1920, the morning after James M. Cox lost the presidential election in a landslide, he sent a one-sentence telegram to the winner, Warren G. Harding.

It said, “In the spirit of America, I accept the decision of the majority, tender as the defeated candidate my congratulations, and pledge as a citizen my support to the executive authority in whatever emergency may arise.”

Cox was a successful journalist, newspaper publisher and governor of Ohio. But as the Democratic candidate for president closely associated with the unpopular incumbent Woodrow Wilson, Cox lost by 404 electoral votes to 127.

Messages like Cox’s telegram are not rare in American history. The American Presidency Project has compiled a handy record of all the concession telegrams and speeches since 1896 when William Jennings Bryan made what was the first of his statements conceding defeat in three presidential elections.

But even though Cox was just one of man…