Who was James Monroe?

A uniter, not a divider

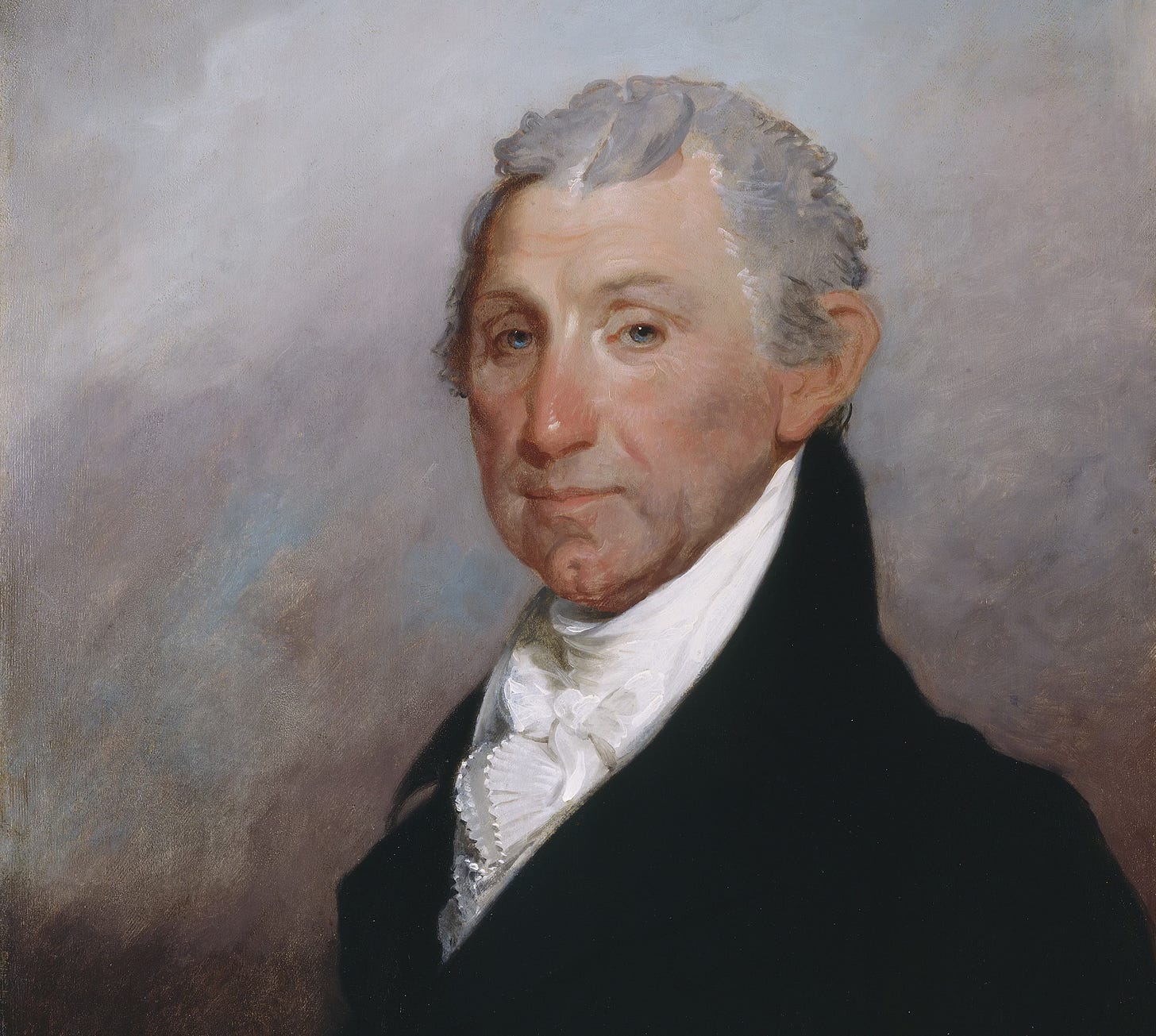

A hero of the American Revolution. A protégé of Thomas Jefferson. A senator. A diplomat. A governor. Secretary of State. Secretary of War. No other American had a resume quite as impressive as that of James Monroe when he ran for president in 1816.

His only glaring weakness as a candidate was that he was another Virginian. Three of the four U.S. presidents to that date were tobacco farmers from his state. Monroe’s candidacy stirred fears of a “Virginia dynasty.”

As Tim McGrath noted in his outstanding 2020 book, James Monroe: A Life, a Vermont newspaper summed up the problem in jest, inventing six reasons to elect Monroe:

1st. He was born in Virginia

2nd. He was educated in Virginia

3rd. He lives in Virginia.

4th. Washington, Jefferson and Madison were and are of Virginia.

5th. He is a friend of Virginia

6th. The last two presidents lived in Virginia.

But Virginia-phobia didn’t keep Monroe from winning the White House in a landslide twice. And while he sometimes is viewed as a lesser member of the founding generation, Monroe had a major hand in shaping the contours of the nation the United States would become — vastly larger than the original 13 colonies.

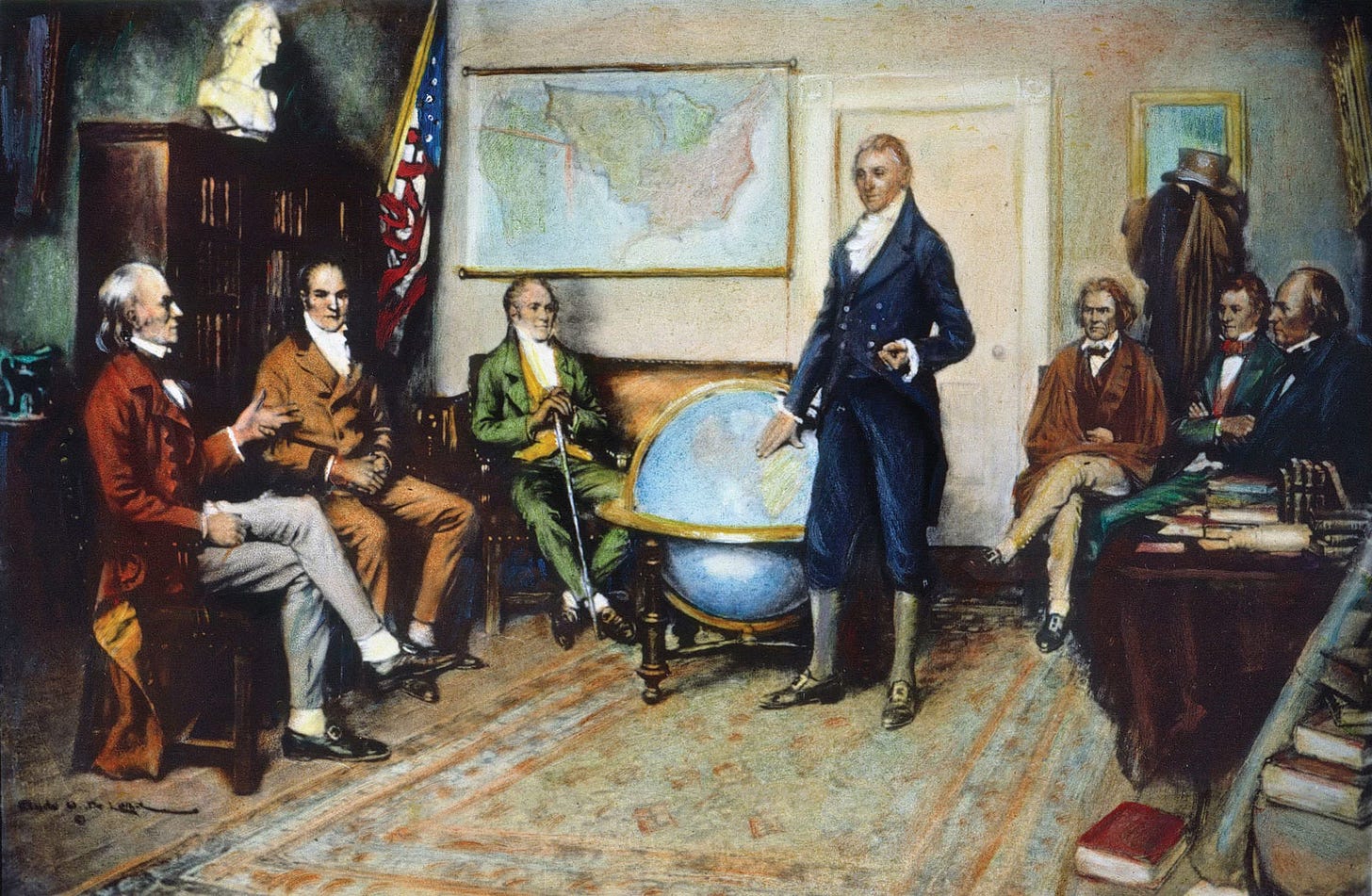

The U.S. seizure of Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro has suddenly drawn attention to James Monroe because of the foreign policy principle he established in 1823. The Monroe Doctrine, crafted by the president and his Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, was a warning to European nations to stay out of the Western Hemisphere in the vacuum created by the liberation of Spain’s former colonies in Latin America.

President Donald Trump called the Monroe Doctrine “a big deal” following his Venezuela mission, but said it had been “superseded” by the “Donroe Doctrine,” picking up a term coined a year ago by a New York Post headline writer. Trump’s doctrine presumably gives him free rein to do whatever he wants in America’s neighborhood, perhaps including a takeover of Greenland.

If Monroe had boasted the way Trump does, he might have erected a triumphal arch in Washington to celebrate his contributions to expanding the United States — his diplomatic work on the Louisiana Purchase, which nearly doubled the size of the country and the acquisitions during his presidency of Florida and the Oregon territory.

That was not his style.

An evolution

As David Sanger noted in the New York Times, Trump displays a portrait of Monroe near his desk in the Oval Office.

Yet it seems unlikely that the president has looked closely at what Monroe actually did as the fifth president. If he had, Trump would have seen the arc of a remarkable story. Here was a man who put his life on the line in the American Revolution, became a ferocious political infighter in the partisan wars of the early republic and then dramatically changed course as he led the nation.

Monroe became “a united, not a divider,” to borrow a phrase that George W. Bush applied to himself when he was running for president in 2000. As it turned out, Bush divided America further, and Trump has ratcheted up the degree of disunity many times.

Their long-ago predecessor Monroe actually walked the walk on bringing people together — so much so, that a Boston newspaper, the Columbian Centinel, called his first term the “Era of Good Feelings.”

Amid the euphoria of victory after his 1816 election — Monroe won 84% of the Electoral College — he saw an opportunity to reorient the presidency itself. In a December 14 letter to then-General Andrew Jackson, he wrote, ”I agree with you decidedly in the principle, that the chief magistrate of the country, ought not to be the head of a party, but of the nation itself.”

As McGrath wrote, “There, in a sentence, was Monroe’s aspiration for his presidency. Throughout his career, this most partisan of politicians had taken the battle to Federalists, often with relish, occasionally with self-importance, at times with vengeance.” But now the model for his presidency wouldn’t be the approach of the partisans Adams and Jefferson; instead it would be that of George Washington.

And Washington hated political parties. In his Farewell Address, at the end of two terms clouded by conflict between the Federalists and Jefferson’s Democratic Republicans, Washington had warned Americans to resist partisanship. Through political parties, he wrote, “cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government…”

A small world

It was no surprise that Monroe felt a kinship to Washington. They shared roots in Westmoreland County, a tobacco-growing region on Virginia’s Northern Neck, which is bounded by the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers. Monroe’s family was comfortable, but not especially affluent.

Monroe’s mother and father died within a two-year period, making the 16-year-old the head of the family, in charge of his sister and three brothers. But he was fortunate to have a politically connected uncle who immediately took the young man under his protection, ensuring that he got a good education.

Like the region’s other planters, the Monroes relied on slave labor for the labor-intensive job of tending the tobacco plants.

The planters’ relationship to the British merchants who bought their crop was especially fraught. As historian T.H. Breen wrote in his book Tobacco Culture, Tidewater Virginia’s planters were “obsessed with the topic of personal debt, a condition that after 1750 seemed to be an inevitable consequence of raising tobacco for a world market. In fact, after 1773 planter indebtedness precipitated a major cultural crisis.” Breen argued that the financial crunch predisposed Virginians to consider revolutionary ideologies they might otherwise have rejected.

Paying off his debts would become a lifelong source of anxiety for Monroe. He greatly expanded his land holdings but could never get above water financially. Slavery too became an increasing concern for him. He recognized its evil and joined other Americans in exploring schemes to send the formerly enslaved to Africa. But as McGrath noted, he freed only one person in his life.

The lieutenant

Monroe was a college student when the colonies confronted Britain and moved toward declaring their independence. Fiercely ambitious, he got caught up in the revolutionary fever and joined a Virginia regiment as a commissioned officer.

“Still a teenager, Monroe looked every inch a lieutenant,” wrote Tim McGrath. “Standing six feet tall, he was lean and fit, with broad, straight shoulders. His face usually carried a serious expression: alert, bright eyes were set above a long nose with a barely perceptible hook, all balanced above a firm jawline ending in a cleft chin. Thoughtfulness and an unassuming demeanor were already established personality traits that would never leave him.”

Eager for battle, Monroe instead experienced mostly retreats as George Washington’s forces fled New York and New Jersey in the face of better trained British troops.

As a junior officer, he was assigned one day to count the colonial rebels’ much reduced troops as they marched by. They were, like his own regiment, “bone weary, their clothing in tatters, their shoes, boots or moccasins worn through, or no shoes at all,” wrote McGrath.

Washington’s surprise

Searching desperately for some way to strike back, Washington ordered a surprise attack, in the midst of a December storm, on the Hessian mercenaries fighting in New Jersey for the British. Monroe volunteered to help lead an advance party toward Trenton, crossing the icy Delaware River.

When the rebel forces reached the enemy’s quarters, Monroe’s superior, a distant cousin of George Washington, was shot and wounded by the Hessians. Monroe took charge and continued down Queen Street, aiming to recapture artillery taken by the enemy.

Then, “a musket ball ripped through Monroe’s upper chest and shoulder. The wound bled profusely—an artery had been severed,” wrote McGrath. “In seconds he grew light-headed and fell into the icy slush on the street. Two or three Virginians carried him straight to Dr. Riker. Seeing Monroe’s wound, he reached into his bag, seized a clamp, and immediately closed off the artery. The doctor’s mere presence kept Monroe from bleeding to death.”

When the battle was over, the revolutionaries saw that their victory was total. The Hessian commander was shot and his surviving troops escaped or surrendered. While only a few Americans were wounded, there were 21 dead Hessians, with 90 injured and more than 900 taken prisoner.

General Washington’s “daring attack exceeded his rosiest expectations,” as McGrath noted. “It was a day he, his army, and succeeding generations of countrymen would forever remember, and certainly young Monroe would not forget, for he carried that musket ball inside him for the rest of his life.”

Battling in war and peace

Monroe enjoyed the support of his former general, Washington, as he set out on a peacetime career. But it was the patronage of another Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, that really launched him into the world of politics and public affairs.

Jefferson schooled Monroe in the practice of law, introduced him to James Madison and corresponded with him constantly for decades. Monroe sought Jefferson’s advice and help on personal and political matters, including the management of his farm. In return, Monroe was an enthusiastic player in the political warfare between Jefferson and the Federalists, in the persons of John Adams and Alexander Hamilton.

Although George Washington sent Monroe to France as a U.S. diplomat, he fell out of favor with the first president over the negotiation of a treaty with Great Britain and was recalled to the U.S.

Later, during Jefferson’s presidency, Monroe helped score a diplomatic triumph in Paris: he was one of two U.S. signatories to the Louisiana Purchase, made possible by the Emperor Napoleon’s need for money for a planned — but never carried out — invasion of Britain.

It was during the administration of President James Madison that Monroe revived his political career on a national platform, first as Secretary of State and then Secretary of War, leading the struggle against the British during the War of 1812. His experience in those roles made him an obvious choice for president in 1816.

Touring America

As president, Monroe selected a geographically and ideologically diverse cabinet, including not only John Quincy Adams from Massachusetts but also John Calhoun of South Carolina.

Then he took another page from George Washington’s textbook. From 1789 through 1791, the first president, had visited the 13 original states, “traveling on horseback and by carriage along rutted dirt roads and over rising rivers,” as a 2021 article in Smithsonian magazine noted. “The president often donned his magnificent Continental Army uniform and rode his favorite white stallion into towns, where he was greeted by cheering citizens. Along the way, he communicated his hopes for the new nation and how he needed everyone’s support to make this vision reality.”

In his tours beginning in 1817, Monroe also hoped to inspire national unity, but he laid out publicly a more prosaic goal: to assess America’s systems of roads, canals and forts. McGrath noted that Monroe packed clothing resembling a Continental Army uniform: a deep blue jacket, buff vest and breeches and a broad-brimmed hat. The crowds responded rapturously to him, much as they had to Washington.

In city after city, local officials and the populace greeted Monroe with banquets and parades. His visits included a sentimental return to the site of his wartime injury in Trenton.

There, McGrath wrote:

Cannons roared and church bells pealed as he was escorted by both dragoons and infantry this time, a fitting addition for the old foot soldier. The sun was setting as he entered town. Tall, erect, shoulders back, with his uniform-like suit and broad hat, he personified the warriors who had attacked the hated Hessians in the snow forty-one years before. To some, he seemed Washington reincarnated; to others he was their father, son, brother, husband, or friend, returned to life and youth if only for a moment’s glance, through eyes brimming with tears.

“Any concerns Monroe” might have had of “an icy welcome in the country’s last bastion of Federalism vanished as his steamship came through Long Island Sound. Countless boats of every size, from revenue cutter to dinghy, were filled to the gunwales with New Englanders, their cheers echoed from ‘the shore thronged with spectators.’”

Calling Monroe’s first term an era of good feelings exaggerates the amity of the time. There were recriminations over the proposed admission of Missouri to the Union as a slave state, and the eventual Missouri Compromise was a pact between the pro- and anti-slavery forces that seemed destined to eventually unravel.

Like other 19th century presidents, Monroe proved largely powerless in the face of a financial crisis — the Panic of 1819.

Still, when it came time for another presidential election in 1820, James Monroe won all but one of the 232 electoral votes—an unimaginable achievement from the standpoint of our own times and one that virtually rivaled George Washington’s winning of all the votes in 1789 and 1792.

One of the electors who voted for Monroe was former president John Adams, father of Monroe’s secretary of state. Jefferson had retired from public life and didn’t vote in the 1820 electoral college but there was no doubt of his support for Monroe.

On July 4, 1826, in “an extraordinary and eerie coincidence,” Adams and Jefferson both died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the document they had fought so hard to bring about.

John Adams’ last words are well known: “Jefferson still lives.” The 83-year-old Jefferson actually had died a few hours earlier than Adams, who was 90.

Less well known is how James Monroe died. Five years later — and remarkably also on July 4 — the fifth president, a 73-year-old suffering from tuberculosis, breathed his last. He lay in a small room at his daughter’s house at Prince and Lafayette Streets in New York City, as the cannons boomed and a parade passed nearby to celebrate Independence Day.

For more on James Monroe:

This is Brilliant, Rich …. Timing as well as Execution ! Bravo !!